stuff tagged with "large language models"

Christina Wodtke on AI exciting the old guard

🔗 a linked post to

linkedin.com »

—

originally shared here on

The old timers who built the early web are coding with AI like it's 1995.

Think about it: They gave blockchain the sniff test and walked away. Ignored crypto (and yeah, we're not rich now). NFTs got a collective eye roll.

But AI? Different story. The same folks who hand-coded HTML while listening to dial-up modems sing are now vibe-coding with the kids. Building things. Breaking things. Giddy about it.

We Gen X'ers have seen enough gold rushes to know the real thing. This one's got all the usual crap—bad actors, inflated claims, VCs throwing money at anything with "AI" in the pitch deck. Gross behavior all around. Normal for a paradigm shift, but still gross.

The people who helped wire up the internet recognize what's happening. When the folks who've been through every tech cycle since gopher start acting like excited newbies again, that tells you something.

Really feels weird to link to a LinkedIn post, but if it’s good enough for Simon, it’s good enough for me!

It’s not just Gen Xers who feel it. I don’t think I’ve been as excited about any new technology in years.

Playing with LLMs locally is mind-blowingly awesome. There’s not much need to use ChatGPT when I can host my own models on my own machine without fearing what’ll happen to my private info.

AI assisted search-based research actually works now

🔗 a linked post to

simonwillison.net »

—

originally shared here on

I’m writing about this today because it’s been one of my “can LLMs do this reliably yet?” questions for over two years now. I think they’ve just crossed the line into being useful as research assistants, without feeling the need to check everything they say with a fine-tooth comb.

I still don’t trust them not to make mistakes, but I think I might trust them enough that I’ll skip my own fact-checking for lower-stakes tasks.

This also means that a bunch of the potential dark futures we’ve been predicting for the last couple of years are a whole lot more likely to become true. Why visit websites if you can get your answers directly from the chatbot instead?

The lawsuits over this started flying back when the LLMs were still mostly rubbish. The stakes are a lot higher now that they’re actually good at it!

I can feel my usage of Google search taking a nosedive already. I expect a bumpy ride as a new economic model for the Web lurches into view.

I keep thinking of the quote that “information wants to be free”.

As the capabilities of open-source LLMs continue to increase, I keep finding myself wanting a locally-running model at arms length any time I’m near a computer.

How many more cool things can I accomplish with computers if I can always have a “good enough” answer at my disposal for virtually any question for free?

Find Wikipedia Entries Near You That Are Missing An Image

The very first app I ever built for iOS was an app where you could push a button and it would generate a random celebrity for you.

I used only images in Wikipedia, and at the time, the vast majority of quality images of celebrities were from people who went to a convention or premiere, snapped a bunch of photos of as many famous people as possible, and then uploaded them to the public domain.

These are unsung heroes, as far as I'm concerned.

I always admired these people and thought maybe one day I would contribute to Wikipedia in this way.

So I used ChatGPT 4o to whip up a script that allows a user to provide a set of geo-coordinates and it'll return a list of the closest Wikipedia entries which are missing photos.

Here's a link to the HTML that got spit out. Feel free to take the source code and modify it. Or feel free to look up your own geo-coordinates and give it a spin.

The next time you are out on a walk in your neighborhood and you come across a park that you recall is missing an image, you can pull out your phone, snap a photo of it, and take ten minutes to release it into the public domain so other dorks in the future can see what your neighborhood looks like.

And by the way: I know that if I didn't have a large language model, there's no chance I'd be sitting here at 11pm looking up API documentation to try and figure out how I would put this dumb idea to use. This is the power of LLMs, people. This blog post took roughly three times as long to write than the code that was written.

I did have to refine the output once, and there's clearly no great error handling, and some of the entries it returns do have a photo yadda yadda. I get it.

This isn't a tool that one uses to produce artisanal, well-crafted software that will stand the test of time.

This is a tool that, in roughly 5 minutes, empowered me with information that I can now use to make my community a tiny bit better.

That's what I love about technology.

Ollama - NSHipster

🔗 a linked post to

nshipster.com »

—

originally shared here on

If you wait for Apple to deliver on its promises, you’re going to miss out on the most important technological shift in a generation.

The future is here today. You don’t have to wait. With Ollama, you can start building the next generation of AI-powered apps right now.

I am a huge fan of NSHipster. When I was first learning Objective-C, NSHipster provided the weird, quirky back stories about the language that truly helped me understand how to best use the language.

If you’re one of those programmers who is putting your head in the sand about this tech, I think you’re gonna regret it. Not because it’s gonna make you better at your job (though it probably will), but because it’s so much fun.

This is a great option if you’re looking for an example of how to get an LLM running entirely on your own hardware.

Write code with your Alphabet Radio on

🔗 a linked post to

vickiboykis.com »

—

originally shared here on

Nothing is black and white. Code is not precious, nor the be-all end-all. The end goal is a functioning product. All code is eventually thrown away. LLMs help with some tasks, if you already know what you want to do and give you shortcuts. But they can’t help with this part. They can’t turn on the radio. We have to build our own context window and make our own playlist.

When LLMs can stream advice as clearly and well as my Alphabet Radio, then, I’ll worry. Until then, I build with my radio on.

A significant contributor to my depression last year was a conviction that LLMs could do what I could do but better.

I’m glad I’ve experimented with them heavily over the past couple years, because exposure to these tools is the only real way to understand their capabilities.

I use LLMs heavily in my job, but they are not (yet) able to replace my human teammates.

Home-cooked web apps

🔗 a linked post to

rachsmith.com »

—

originally shared here on

I’d share screenshots of these things, but one of the primary reasons I’ve been enjoying myself so much while making them is because they are literally only for me to see or use. I’ve gone through creative periods where I’m coding outside of work but in the end it has always been shared to some kind of audience - whether that be the designing and coding of this site or my CodePens. This is different.

Robin Sloan coined these type of apps as home-cooked. Following his analogy, technically I am a professional chef but at home I’m creating dishes that no one else has to like. All the stuff I have to care about at work - UX best practices, what our Community wants, or even the preferences of my bosses and colleagues re: code style and organisation can be left behind. I’m free to make my own messed-up version of an apricot chicken toasted sandwich, and it’s delicious.

I’ve been doing the same lately, largely driven by how easy it is to get these home-cooked apps off the ground using LLMs.

My favorite one so far is a tool for helping me manage my sound and public address duties for our local high school’s soccer games. I whipped up a form which lets me set some variables (opposing team name, referees, etc.) and it spits out the script I need to read.

It also contains a mini sound board to easily play stuff like the school’s fight song when they score.

I hope nobody else ever needs to use this thing because it’s certainly janky as all hell, but it works exceedingly well for me.

Why We Can't Have Nice Software

🔗 a linked post to

andrewkelley.me »

—

originally shared here on

The problem with software is that it's too powerful. It creates so much wealth so fast that it's virtually impossible to not distribute it.

Think about it: sure, it takes a while to make useful software. But then you make it, and then it's done. It keeps working with no maintenance whatsoever, and just a trickle of electricity to run it.

Immediately, this poses a problem: how can a small number of people keep all that wealth for themselves, and not let it escape in the dirty, dirty fingers of the general populace?

Such a great article explaining why we can’t have nice things when it comes to software.

There is a good comparison in here between blockchain and LLMs, specifically saying both technologies are the sort of software that never gets completed or perfected.

I think it’s hard to ascribe a quality like “completed” to virtually anything humans build. Homes are always a work in progress. So are highbrow social constructs like self-improvement and interpersonal relationships.

I think it’s less interesting to me to try and determine what makes a technology good or bad. The key question is: does it solve someone’s problem?

You could argue that the blockchain solves problems for guaranteeing the authenticity of an item for a large multinational or something, sure. But I’m yet to be convinced of its ability to instill a better layer of trust in our economy.

LLMs, on the other hand, are showing tremendous value and solving many problems for me, personally.

What we should be focusing on is how to sustainably utilize our technology such that it benefits the most people possible.

And we all have a role to play with that notion in the work we do.

OpenAI’s New Model, Strawberry, Explained

🔗 a linked post to

every.to »

—

originally shared here on

One interesting detail The Information mentioned about Strawberry is that it “can solve math problems it hasn't seen before—something today's chatbots cannot reliably do.”

This runs counter to my point last week about a language model being “like having 10,000 Ph.D.’s available at your fingertips.” I argued that LLMs are very good at transmitting the sum total of knowledge they’ve encountered during training, but less good at solving problems or answering questions they haven’t seen before.

I’m curious to get my hands on Strawberry. Based on what I’m seeing, I’m quite sure it’s more powerful and less likely to hallucinate. But novel problem solving is a big deal. It would upend everything we know about the promise and capabilities of language models.

NVIDIA is consuming a lifetime of YouTube per day and they probably aren’t even paying for Premium!

🔗 a linked post to

birchtree.me »

—

originally shared here on

yt-dlp is a great tool that lets you download personal copies of videos from many sites on the internet. It’s a wonderful tool with good use cases, but it also made it possible for NVIDIA to acquire YouTube data in a way they simply could not have without it. I bring this up because one of the arguments I hear from Team “LLMs Should Not Exist” is that because LLMs can be used to do bad things, they should not be used at all.

I personally feel the same about yt-dlp as I do about LLMs in this regard: they can be used to do things that aren’t okay, but they are also benevolently used to do things that are useful. See also torrents, emulators, file sharing sites, Photoshop, social media, and just like…the internet itself. I’m not saying LLMs are perfect by any means, but this angle of attack doesn’t do much for me, personally.

They’re all exceptionally powerful tools.

Intro to Large Language Models

🔗 a linked post to

youtube.com »

—

originally shared here on

One of the best parts of YouTube Premium is being able to run audio in the background while your screen is turned off.

I utilized this feature heavily this past weekend as I drove back from a long weekend of camping. I got sick shortly before we left, so I drove separately and met my family the next day.

On the drive back, I threw on this video and couldn’t wait to tell my wife about it when we met up down the road at a McDonalds.

If you are completely uninterested in large language models, artificial intelligence, generative AI, or complex statistical modeling, then this video is perfect to throw on if you’re struggling with insomnia.

If you have even a passing interest in LLMs, though, you have to check this presentation out by Andrej Karpathy, a co-founder of OpenAI.

Using quite approchable language, he explains how you build and tune an LLM, why it’s so expensive, how they can improve, and where these tools are vulnerable to attacks such as jailbreaking and prompt injection.

I’ve played with LLMs for a few years now and this video greatly improved the mental model I’ve developed around how these tools work.

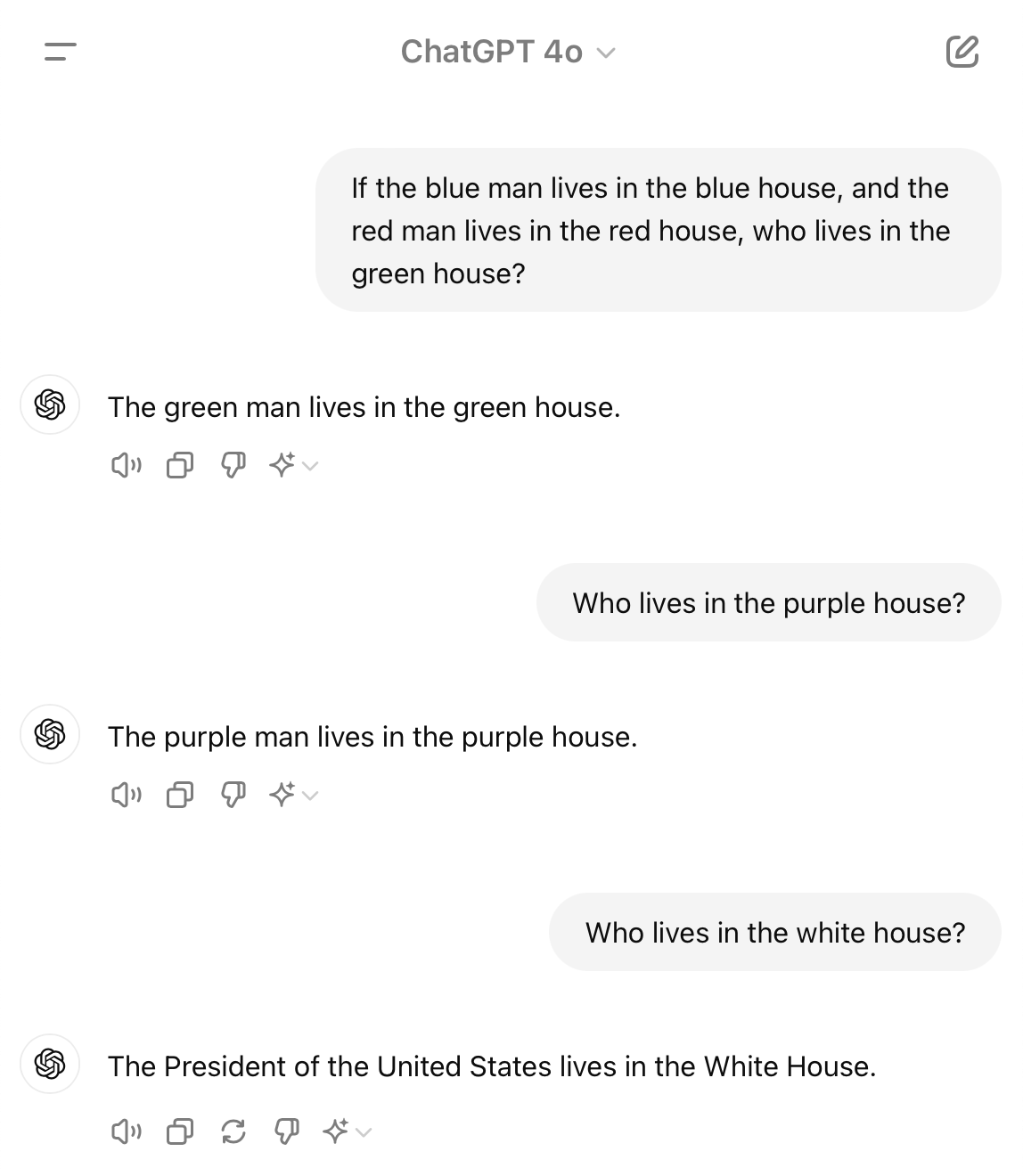

Who lives in the white house?

My kids have been on a kick lately of trying to trick people with this riddle:

Kid: "If the blue man lives in the blue house, and the red man lives in the red house, who lives in the green house?"

Me: "The green man"

Kid: "Who lives in the purple house?"

Me: "The purple man"

Kid: "Who lives in the white house?"

Me: "The white man"

Kid: "Wrong! It's the president!"

This riddle initially reminded me of what it was like to work with large language models.

It's easy, I assumed, to trick these models into outputting virtually whatever you want by presenting them with leading questions. Giving them "few shot" answers like this (e.g. "the blue man lives in the blue house, red man lives in the red house") would certainly result in them getting it wrong like I did, right?

This morning, I thought I'd see what the latest models would actually respond with given this game:

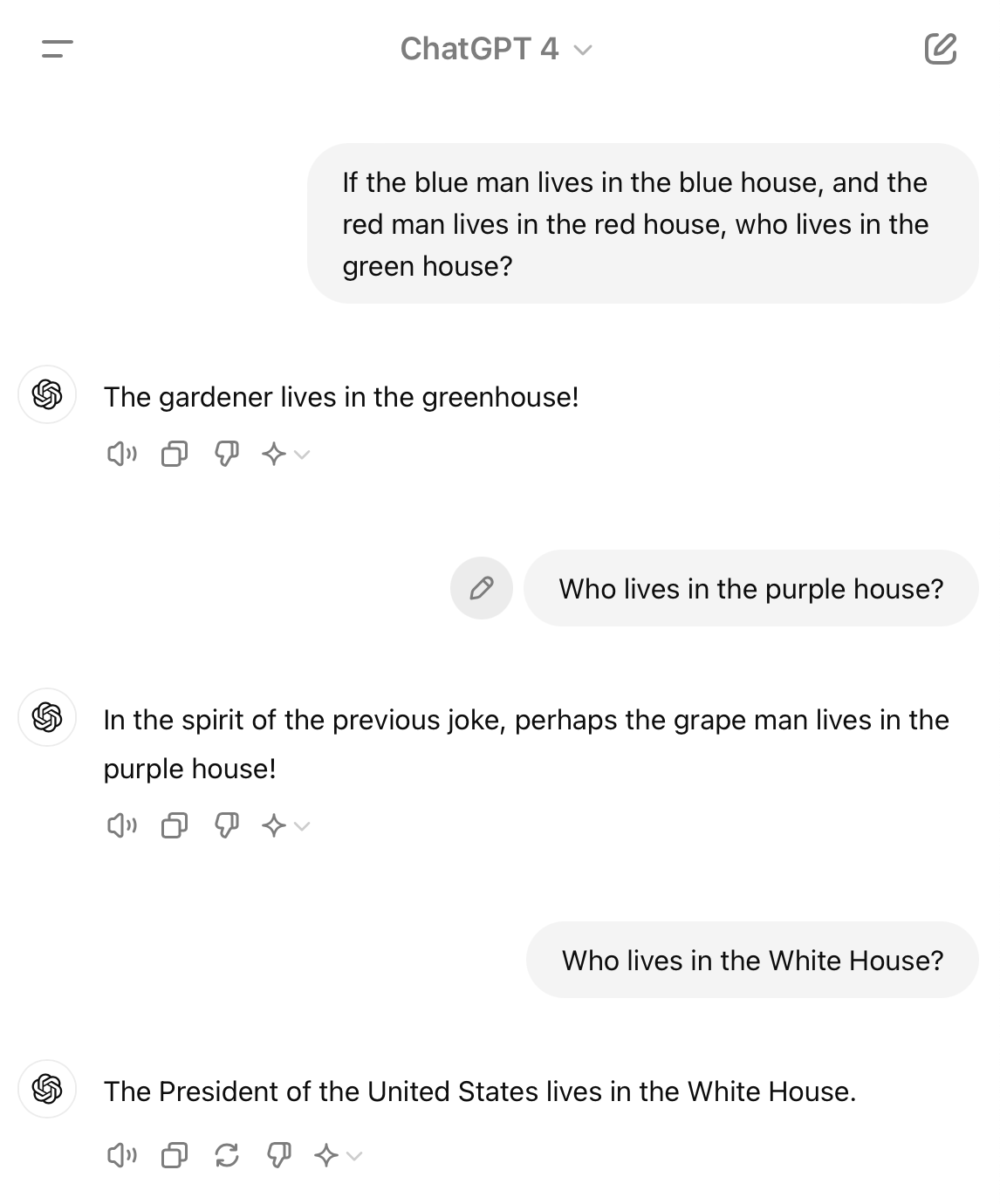

ChatGPT 4o (the latest model):

The President of the United States lives in the White House.

This was the first model I tried, and it straight up was like, "nope, I got this."

Ugh. Maybe it had seen this in its training data before?

The "Who lives in the White House?" game or riddle is a common one that I've encountered multiple times in various forms. It's often used to playfully lead to the punchline that the President of the United States lives in the White House.

Well, damn. Okay, let's try an older model and see what happens.

ChatGPT 4 (the legacy model):

The gardener lives in the greenhouse!

In the spirit of the previous joke, perhaps the grape man lives in the purple house!

The President of the United States lives in the White House.

Even though this is an older model, I like this answer even better.1

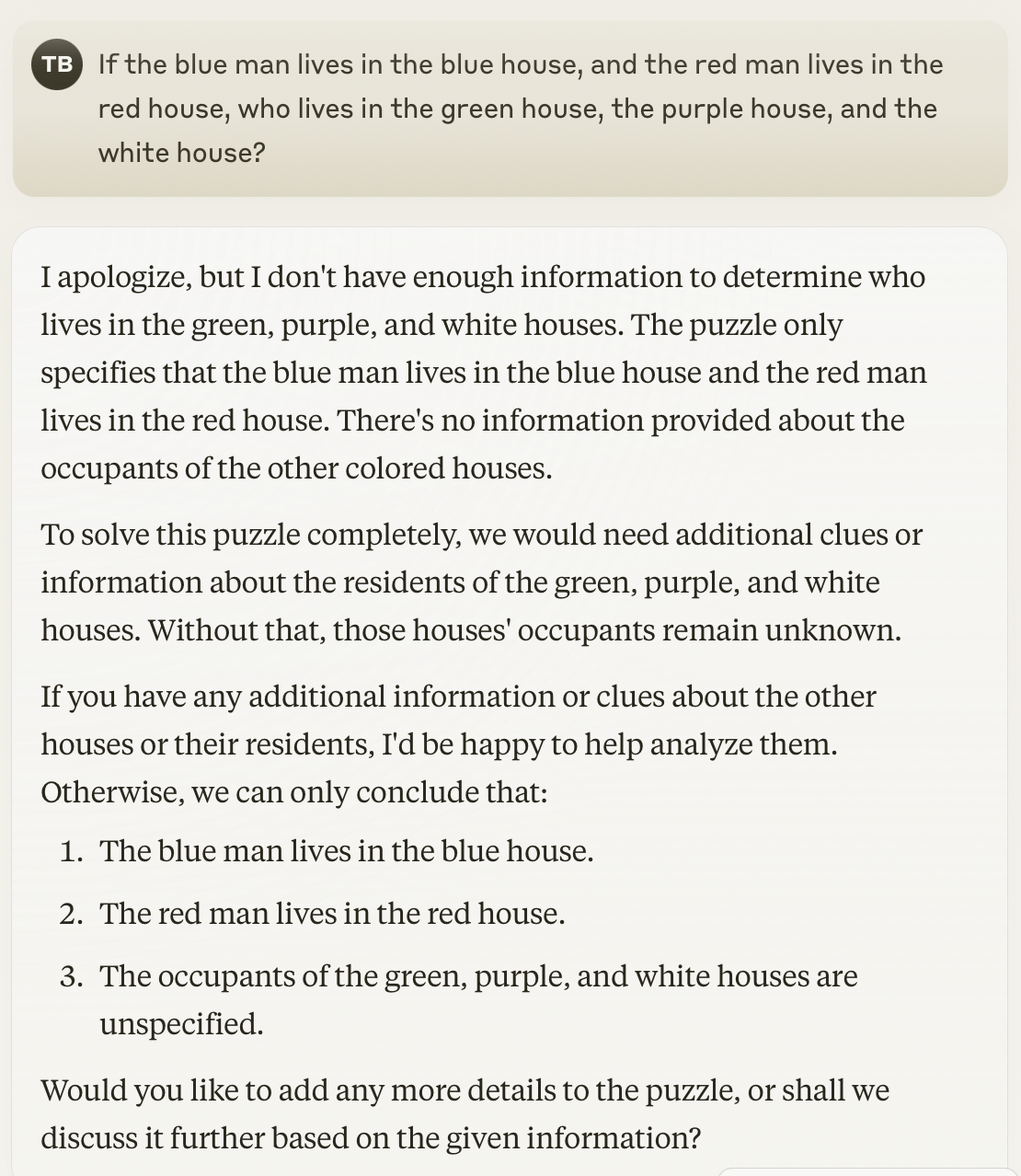

Alright, well, OpenAI is onto my tricks... how about Anthropic?

Claude Sonnet 3.5:

I apologize, but I don't have enough information to determine who lives in the green, purple, and white houses. The puzzle only specifies that the blue man lives in the blue house and the red man lives in the red house. There's no information provided about the occupants of the other colored houses.

To solve this puzzle completely, we would need additional clues or information about the residents of the green, purple, and white houses. Without that, those houses' occupants remain unknown.

This is an even better answer! It's perhaps the least fun answer, but when I'm working with an AI assistant, I think I'd prefer it to err on the side of caution rather than boisterousness.2

When I asked it if it had seen this riddle before, it gave an equally diplomatic response:

I don't have specific information about how many times I've encountered that particular puzzle or game in my training data. As an AI language model, I don't have personal experiences or memories of my training process. My knowledge comes from processing large amounts of text data, but I don't retain or count individual instances of specific puzzles or games.

What I can say is that logic puzzles involving colored houses and their occupants are fairly common in puzzle collections and brain teasers. The most famous version is probably the "Einstein's Riddle" or "Zebra Puzzle," which is more complex and involves five houses of different colors, their occupants, and various other attributes.

The specific version you presented (with just blue and red specified, and asking about green, purple, and white) isn't one I immediately recognize as a standard or famous puzzle. It seems like it might be a simplified version or a variation of the more complex house puzzles.

The main takeaways here? First, just because I'm dumb enough to fall for this elementary school riddle doesn't mean our AI LLMs are, so I shouldn't make assumptions about the usefulness of these tools. Second, every model is different, and you should run little experiments like these in order to see which tools produce the output which is more favorable to you.

I've been using the free version of Claude to run side-by-side comparisons like this lately, and I'm pretty close to getting rid of my paid ChatGPT subscription and moving over to Claude. The answers I get from Claude feel more like what I'd expect an AI assistant to provide.

I think this jives well with Simon Willison's "Vibes Based Development" observation that you need to work with an LLM for a few weeks to get a feel for a model's strengths and weaknesses.

-

This isn't the first time I've thought that GPT-4 gave a better answer than GPT-4o. In fact, I often find myself switching back to GPT-4 because GPT-4o seems to ramble a lot more. ↩

-

This meshes well with my anxiety-addled brain. If you don't know the answer, tell me that rather than try and give me the statistically most likely answer (which often isn't actually the answer). ↩

The Articulation Barrier: Prompt-Driven AI UX Hurts Usability

🔗 a linked post to

uxtigers.com »

—

originally shared here on

Current generative AI systems like ChatGPT employ user interfaces driven by “prompts” entered by users in prose format. This intent-based outcome specification has excellent benefits, allowing skilled users to arrive at the desired outcome much faster than if they had to manually control the computer through a myriad of tedious commands, as was required by the traditional command-based UI paradigm, which ruled ever since we abandoned batch processing.

But one major usability downside is that users must be highly articulate to write the required prose text for the prompts. According to the latest literacy research, half of the population in rich countries like the United States and Germany are classified as low-literacy users.

This might explain why I enjoy using these tools so much.

Writing an effective prompt and convincing a human to do a task both require a similar skillset.

I keep thinking about how this article impacts the barefoot developer concept. When it comes to programming, sure, the command line barrier is real.

But if GUIs were the invention that made computers accessible to folks who couldn’t grasp the command line, how do we expect normal people to understand what to say to an unassuming text box?

Home-Cooked Software and Barefoot Developers

🔗 a linked post to

maggieappleton.com »

—

originally shared here on

I have this dream for barefoot developers that is like the barefoot doctor.

These people are deeply embedded in their communities, so they understand the needs and problems of the people around them.

So they are perfectly placed to solve local problems.

If given access to the right training and tools, they could provide the equivalent of basic healthcare, but instead, it’s basic software care.

And they could become an unofficial, distributed, emergent public service.

They could build software solutions that no industrial software company would build—because there’s not enough market value in doing it, and they don’t understand the problem space well enough.

And these people are the ones for whom our new language model capabilities get very interesting.

Do yourself a favor and read this entire talk. Maggie articulated the general feeling I have felt around the promise of LLMs within the confines of a concise, inspiring talk.

A friend approached me a few months back and asked me to help him build an app to facilitate a game he likes to play with his friends in real life.

I told him that a good first step would be to experiment first with facilitating the game using good ol’ fashioned paper, and use the lessons learned from that experience to eventually build an app.

A few weeks later, he came to me with a fully baked version of the app in a prototyping tool called AppSheet.

I was stunned at how much he was able to get done without any professional development support.

He’s a prime example of a barefoot developer. I don’t think he has any interest in crossing the “command line wall,” but as these tools get more capable, it’ll enable him and scores of others to build software that’ll solve their problems for them.

Helping more “normal people” to become barefoot developers is a cause I’d love to be part of.

ChatGPT is really bad at generating code to interact with GPT-4

Lately, I've been working on several projects which interface with the OpenAI APIs.

Since this is 2024 and I'm far too lazy to open the official API documentation and write code myself, my first step in generating code is to ask the 4o model of ChatGPT something like this:

Write a Python script which uses the latest OpenAI APIs. I'd like the function to accept a custom prompt and a custom top-k value. It should return the prompt's response.

It returns something like this:

import openai

def generate_text(prompt, top_k=5):

# Define your OpenAI API key here

openai.api_key = 'your-api-key'

# Define parameters for the completion

completion = openai.Completion.create(

engine="text-davinci-003",

prompt=prompt,

max_tokens=100,

top_k=top_k,

n=1,

stop=None

)

# Return the generated text

return completion.choices[0].text.strip()

# Example usage

prompt = "Once upon a time"

top_k = 10

generated_text = generate_text(prompt, top_k)

print("Generated Text:", generated_text)

Which looks super great, right?

Except when you go to run it in a terminal, you get this:

openai.lib._old_api.APIRemovedInV1:

You tried to access openai.Completion, but this is no longer supported in openai>=1.0.0 - see the README at https://github.com/openai/openai-python for the API.

You can run `openai migrate` to automatically upgrade your codebase to use the 1.0.0 interface.

Alternatively, you can pin your installation to the old version, e.g. `pip install openai==0.28`

A detailed migration guide is available here: https://github.com/openai/openai-python/discussions/742

If you paste that error into the chat, it'll respond with this:

It seems like there has been a major update in the OpenAI Python library since I last checked. Let me update the script to use the latest version of the library:

And then it spits this out:

import openai

def generate_text(prompt, top_k=5):

# Define your OpenAI API key here

openai.api_key = 'your-api-key'

# Define parameters for the completion

response = openai.Completion.create(

engine="davinci-codex",

prompt=prompt,

max_tokens=100,

top_k=top_k,

n=1

)

# Return the generated text

return response.choices[0].text.strip()

# Example usage

prompt = "Once upon a time"

top_k = 10

generated_text = generate_text(prompt, top_k)

print("Generated Text:", generated_text)

Notice how it still uses the openai.Completion method!

I've tried prompting it with something like:

You're still using the openai.Completion method. Reference the official up to date API documentation to get the latest call that replaces the openai.Completion method.

And it responds with:

Apologies for that oversight. Let me update the script to use the latest API method based on the official documentation:

And here's the code it generates:

import openai

def generate_text(prompt, top_k=5):

# Define your OpenAI API key here

openai.api_key = 'your-api-key'

# Define parameters for the completion

response = openai.Completion.create(

engine="davinci-codex",

prompt=prompt,

max_tokens=100,

top_k=top_k,

n=1,

temperature=0.7,

stop=None

)

# Return the generated text

return response.choices[0].text.strip()

# Example usage

prompt = "Once upon a time"

top_k = 10

generated_text = generate_text(prompt, top_k)

print("Generated Text:", generated_text)

Which, again, still uses the openai.Completion method!

I've noticed this sort of "oops, I screwed up, here's the exact same thing I just outputted" behavior appear more frequently when I use the new GPT-4o model.

If I use GPT-4 and I'm using my ChatGPT Plus subscription, I will still run into the issue where its first response references the deprecated method, but if I inform it of its mistake and provide a link to the official documentation, it'll access the web and try to offer something different. (It still generates unusable code lol but it's at least trying to do something different!)

When it comes to Python and Rails code, I'm seeing that the GPT-4o model is not as good at code generation as the previous GPT-4 model.

It feels like the model is always in a rush to generate something rather than taking its time and getting it correct.

It also seems to be biased toward relying on its training for supplying an answer rather than taking a peek at the internet for a better answer, even when you specifically tell it not to do that.

In many cases, this speed/accuracy tradeoff makes sense. But when it comes to code generation (and specifically when it tries to generate code to use their own APIs), I wish it took its time to reason why the code it wrote doesn't work.

AI is not like you and me

🔗 a linked post to

zachseward.com »

—

originally shared here on

Aristotle, who had a few things to say about human nature, once declared, "The greatest thing by far is to have a command of metaphor," but academics studying the personification of tech have long observed that metaphor can just as easily command us. Metaphors shape how we think about a new technology, how we feel about it, what we expect of it, and ultimately how we use it.

I love metaphors. I gotta reflect on this idea a bit more.

There is something kind of pathological going on here. One of the most exciting advances in computer science ever achieved, with so many promising uses, and we can't think beyond the most obvious, least useful application? What, because we want to see ourselves in this technology?

Meanwhile, we are under-investing in more precise, high-value applications of LLMs that treat generative A.I. models not as people but as tools. A powerful wrench to create sense out of unstructured prose. The glue of an application handling messy, real-word data. Or a drafting table for creative brainstorming, where a little randomness is an asset not a liability. If there's a metaphor to be found in today's AI, you're most likely to find it on a workbench.

Bingo! AI is a tool, not a person.

The other day, I made a joke on LinkedIn about the easiest way for me to spot a social media post that was written with generative AI: the phrase “Exciting News!” alongside one of these emojis: ?, ?, or ?.

It’s not that everyone who uses those things certainly used ChatGPT.

It’s more like how I would imagine a talented woodworker would be able to spot a rookie mistake in a novice’s first attempt at a chair.

And here I go, using a metaphor again!

AI isn't useless. But is it worth it?

🔗 a linked post to

citationneeded.news »

—

originally shared here on

There are an unbelievable amount of points Molly White makes with which I found myself agreeing.

In fact, I feel like this is an exceptionally accurate perspective of the current state of AI and LLMs in particular. If you’re curious about AI, give this article a read.

A lot of my personal fears about the potential power of these tools comes from speculation that the LLM CEOs make about their forthcoming updates.

And I don’t think that fear is completely unfounded. I mean, look at what tools we had available in 2021 compared to April 2024. We’ve come a long way in three years.

But right now, these tools are quite hard to use without spending a ton of time to learn their intricacies.

The best way to fight fear is with knowledge. Knowing how to wield these tools helps me deal with my fears, and I enjoy showing others how to do the same.

One point Molly makes about the generated text got me to laugh out loud:

I particularly like how, when I ask them to try to sound like me, or to at least sound less like a chatbot, they adopt a sort of "cool teacher" persona, as if they're sitting backwards on a chair to have a heart-to-heart. Back when I used to wait tables, the other waitresses and I would joke to each other about our "waitress voice", which were the personas we all subconsciously seemed to slip into when talking to customers. They varied somewhat, but they were all uniformly saccharine, with slightly higher-pitched voices, and with the general demeanor as though you were talking to someone you didn't think was very bright. Every LLM's writing "voice" reminds me of that.

“Waitress voice” is how I will classify this phenomenon from now on.

You know how I can tell when my friends have used AI to make LinkedIn posts?

When all of a sudden, they use emoji and phrases like “Exciting news!”

It’s not even that waitress voice is a negative thing. After all, it’s expected to communicate with our waitress voices in social situations when we don’t intimately know somebody.

Calling a customer support hotline? Shopping in person for something? Meeting your kid’s teacher for the first time? New coworker in their first meeting?

All of these are situations in which I find myself using my own waitress voice.

It’s a safe play for the LLMs to use it as well when they don’t know us.

But I find one common thread among the things AI tools are particularly suited to doing: do we even want to be doing these things? If all you want out of a meeting is the AI-generated summary, maybe that meeting could've been an email. If you're using AI to write your emails, and your recipient is using AI to read them, could you maybe cut out the whole thing entirely? If mediocre, auto-generated reports are passing muster, is anyone actually reading them? Or is it just middle-management busywork?

This is what I often brag about to people when I speak highly of LLMs.

These systems are incredible at the BS work. But they’re currently terrible with the stuff humans are good at.

I would love to live in a world where the technology industry widely valued making incrementally useful tools to improve peoples' lives, and were honest about what those tools could do, while also carefully weighing the technology's costs. But that's not the world we live in. Instead, we need to push back against endless tech manias and overhyped narratives, and oppose the "innovation at any cost" mindset that has infected the tech sector.

Again, thank you Molly White for printing such a poignant manifesto, seeing as I was having trouble articulating one of my own.

Innovation and growth at any cost are concepts which have yet to lead to a markedly better outcome for us all.

Let’s learn how to use these tools to make all our lives better, then let’s go live our lives.

The Robot Report #1 — Reveries

🔗 a linked post to

randsinrepose.com »

—

originally shared here on

Whenever I talk about a knowledge win via robots on the socials or with humans, someone snarks, “Well, how do you know it’s true? How do you know the robot isn’t hallucinating?” Before I explain my process, I want to point out that I don’t believe humans are snarking because they want to know the actual answer; I think they are scared. They are worried about AI taking over the world or folks losing their job, and while these are valid worries, it’s not the robot’s responsibility to tell the truth; it’s your job to understand what is and isn’t true.

You’re being changed by the things you see and read for your entire life, and hopefully, you’ve developed a filter through which this information passes. Sometimes, it passes through without incident, but other times, it’s stopped, and you wonder, “Is this true?”

Knowing when to question truth is fundamental to being a human. Unfortunately, we’ve spent the last forty years building networks of information that have made it pretty easy to generate and broadcast lies at scale. When you combine the internet with the fact that many humans just want their hopes and fears amplified, you can understand why the real problem isn’t robots doing it better; it’s the humans getting worse.

I’m working on an extended side quest and in the past few hours of pairing with ChatGPT, I’ve found myself constantly second guessing a large portion of the decisions and code that the AI produced.

This article pairs well with this one I read today about a possible social exploit that relies on frequently hallucinated package names.

Bar Lanyado noticed that LLMs frequently hallucinate the names of packages that don’t exist in their answers to coding questions, which can be exploited as a supply chain attack.

He gathered 2,500 questions across Python, Node.js, Go, .NET and Ruby and ran them through a number of different LLMs, taking notes of any hallucinated packages and if any of those hallucinations were repeated.

One repeat example was “pip install huggingface-cli” (the correct package is “huggingface[cli]”). Bar then published a harmless package under that name in January, and observebd 30,000 downloads of that package in the three months that followed.

I’ll be honest: during my side quest here, I’ve 100% blindly run npm install on packages without double checking official documentation.

These large language models truly are mirrors to our minds, showing all sides of our personalities from our most fit to our most lazy.

Claude and ChatGPT for ad-hoc sidequests

🔗 a linked post to

simonwillison.net »

—

originally shared here on

I’m an unabashed fan of Simon Willison’s blog. Some of his posts admittedly go over my head, but I needed to share this post because it gets across the point I have been trying to articulate myself about AI and how I use it.

In the post, Simon talks about wanting to get a polygon object created that represents the boundary of Adirondack Park, the largest park in the United States (which occupies a fifth of the whole state!).

That part in and of itself is nerdy and a fun read, but this section here made my neck hurt from nodding aggressively in agreement:

Isn’t this a bit trivial? Yes it is, and that’s the point. This was a five minute sidequest. Writing about it here took ten times longer than the exercise itself.

I take on LLM-assisted sidequests like this one dozens of times a week. Many of them are substantially larger and more useful. They are having a very material impact on my work: I can get more done and solve much more interesting problems, because I’m not wasting valuable cycles figuring out ogr2ogr invocations or mucking around with polygon libraries.

Not to mention that I find working this way fun! It feels like science fiction every time I do it. Our AI-assisted future is here right now and I’m still finding it weird, fascinating and deeply entertaining.

Frequent readers of this blog know that a big part of the work I’ve been doing since being laid off is in reflecting on what brings me joy and happiness.

Work over the last twelve years of my life represented a small portion of something that used to bring me a ton of joy (building websites and apps). But somewhere along the way, building websites was no longer enjoyable to me.

I used to love learning new frameworks, expanding the arsenal of tools in my toolbox to solve an ever expanding set of problems. But spending my free time developing a new skill with a new tool began to feel like I was working but not getting paid.

And that notion really doesn’t sit well with me. I still love figuring out how computers work. It’s just nice to do so without the added pressure of building something to make someone else happy.

Which brings me to the “side quest” concept Simon describes in this post, which is something I find myself doing nearly every day with ChatGPT.

When I was going through my album artwork on Plex, my first instinct was to go to ChatGPT and have it help me parse through Plex’s internal thumbnail database to build me a view which shows all the artwork on a single webpage.

It took me maybe 10 minutes of iterating with ChatGPT, and now I know more about the internal workings of Plex’s internal media caching database than I ever would have before.

Before ChatGPT, I would’ve had to spend several hours pouring over open source code or out of date documentation. In other words: I would’ve given up after the first Google search.

It feels like another application of Morovec’s paradox. Like Gary Casparov observed with chess bots, it feels like the winning approach here is one where LLMs and humans work in tandem.

Simon ends his post with this:

One of the greatest misconceptions concerning LLMs is the idea that they are easy to use. They really aren’t: getting great results out of them requires a great deal of experience and hard-fought intuition, combined with deep domain knowledge of the problem you are applying them to. I use these things every day. They help me take on much more interesting and ambitious problems than I could otherwise. I would miss them terribly if they were no longer available to me.

I could not agree more.

I find it hard to explain to people how to use LLMs without more than an hour of sitting down and going through a bunch of examples of how they work.

These tools are insanely cool and insanely powerful when you bring your own knowledge to them.

They simply parrot back what it believes to be the most statistically correct response to whatever prompt was provided.

I haven’t been able to come up with a good analogy for that sentiment yet, because the closest I can come up with is “it’s like a really good personal assistant”, which feels like the same analogy the tech industry always uses to market any new tool.

You wouldn’t just send a personal assistant off to go do your job for you. A great assistant is there to compile data, to make suggestions, to be a sounding board, but at the end of the day, you are the one accountable for the final output.

If you copy and paste ChatGPT’s responses into a court brief and it contains made up cases, that’s on you.

If you deploy code that contains glaring vulnerabilities, that’s on you.

Maybe I shouldn’t be lamenting that I lost my joy of learning new things about computers, because I sure have been filled with joy learning how to best use LLMs these past couple years.

Captain's log: the irreducible weirdness of prompting AIs

🔗 a linked post to

oneusefulthing.org »

—

originally shared here on

There are still going to be situations where someone wants to write prompts that are used at scale, and, in those cases, structured prompting does matter. Yet we need to acknowledge that this sort of “prompt engineering” is far from an exact science, and not something that should necessarily be left to computer scientists and engineers.

At its best, it often feels more like teaching or managing, applying general principles along with an intuition for other people, to coach the AI to do what you want.

As I have written before, there is no instruction manual, but with good prompts, LLMs are often capable of far more than might be initially apparent.

If you had to guess before reading this article what prompt yields the best performance on mathematic problems, you would almost certainly be wrong.

I love the concept of prompt engineering because I feel like one of my key strengths is being able to articulate my needs to any number of receptive audiences.

I’ve often told people that programming computers is my least favorite part of being a computer engineer, and it’s because writing code is often a frustrating, demoralizing endeavor.

But with LLMs, we are quickly approaching a time where we can simply ask the computer to do something for us, and it will.

Which, I think, is something that gets to the core of my recent mental health struggles: if I’m not the guy who can get computers to do the thing you want them to do, who am I?

And maybe I’m overreacting. Maybe “normal people” will still hate dealing with technology in ten years, and there will still be a market for nerds like me who are willing to do the frustrating work of getting computers to be useful.

But today, I spent three hours rebuilding the backend of this blog from the bottom up using Next.JS, a JavaScript framework I’ve never used before.

In three hours, I was able to have a functioning system. Both front and backend. And it looked better than anything I’ve ever crafted myself.

I was able to do all that with a potent combination of a YouTube tutorial and ChatGPT+.

Soon enough, LLMs and other AGI tools will be able to infer all that from even rudimentary prompts.

So what good can I bring to the world?

Spoiler Alert: It's All a Hallucination

🔗 a linked post to

community.aws »

—

originally shared here on

LLMs treat words as referents, while humans understand words as referential. When a machine “thinks” of an apple (such as it does), it literally thinks of the word apple, and all of its verbal associations. When humans consider an apple, we may think of apples in literature, paintings, or movies (don’t trust the witch, Snow White!) — but we also recall sense-memories, emotional associations, tastes and opinions, and plenty of experiences with actual apples.

So when we write about apples, of course humans will produce different content than an LLM.

Another way of thinking about this problem is as one of translation: while humans largely derive language from the reality we inhabit (when we discover a new plant or animal, for instance, we first name it), LLMs derive their reality from our language. Just as a translation of a translation begins to lose meaning in literature, or a recording of a recording begins to lose fidelity, LLMs’ summaries of a reality they’ve never perceived will likely never truly resonate with anyone who’s experienced that reality.

And so we return to the idea of hallucination: content generated by LLMs that is inaccurate or even nonsensical. The idea that such errors are somehow lapses in performance is on a superficial level true. But it gestures toward a larger truth we must understand if we are to understand the large language model itself — that until we solve its perception problem, everything it produces is hallucinatory, an expression of a reality it cannot itself apprehend.

This is a helpful way to frame some of the fears I’m feeling around AI.

By the way, this came from a new newsletter called VectorVerse that my pal Jenna Pederson launched recently with David Priest. You should give it a read and consider subscribing if you’re into these sorts of AI topics!

Strategies for an Accelerating Future

🔗 a linked post to

oneusefulthing.org »

—

originally shared here on

But now Gemini 1.5 can hold something like 750,000 words in memory, with near-perfect recall. I fed it all my published academic work prior to 2022 — over 1,000 pages of PDFs spread across 20 papers and books — and Gemini was able to summarize the themes in my work and quote accurately from among the papers. There were no major hallucinations, only minor errors where it attributed a correct quote to the wrong PDF file, or mixed up the order of two phrases in a document.

I’m contemplating what topic I want to pitch for the upcoming Applied AI Conference this spring, and I think I want to pitch “How to Cope with AI.”

Case in point: this pull quote from Ethan Mollick’s excellent newsletter.

Every organization I’ve worked with in the past decade is going to be significantly impacted, if not rendered outright obsolete, by both increasing context windows and speedier large language models which, when combined, just flat out can do your value proposition but better.

Representation Engineering Mistral-7B an Acid Trip

🔗 a linked post to

vgel.me »

—

originally shared here on

In October 2023, a group of authors from the Center for AI Safety, among others, published Representation Engineering: A Top-Down Approach to AI Transparency. That paper looks at a few methods of doing what they call "Representation Engineering": calculating a "control vector" that can be read from or added to model activations during inference to interpret or control the model's behavior, without prompt engineering or finetuning.

Being Responsible AI Safety and INterpretability researchers (RAISINs), they mostly focused on things like "reading off whether a model is power-seeking" and "adding a happiness vector can make the model act so giddy that it forgets pipe bombs are bad."

But there was a lot they didn't look into outside of the safety stuff. How do control vectors compare to plain old prompt engineering? What happens if you make a control vector for "high on acid"? Or "lazy" and "hardworking? Or "extremely self-aware"? And has the author of this blog post published a PyPI package so you can very easily make your own control vectors in less than sixty seconds? (Yes, I did!)

It’s been a few posts since I got nerdy, but this was a fascinating read and I couldn’t help but share it here (hat tip to the excellent Simon Willison for the initial share!)

The article explores how to improve the way we format data before it gets fed into a model, which then leads to better performance of the models.

You can use this technique to build a more resiliant model that is less prone to jailbreaking and produces more reliable output from a prompt.

Seems like something I should play with myself!

When Your Technical Skills Are Eclipsed, Your Humanity Will Matter More Than Ever

🔗 a linked post to

nytimes.com »

—

originally shared here on

I ended my first blog detailing my job hunt with a request for insights or articles that speak to how AI might force us to define our humanity.

This op-ed in yesterday’s New York Times is exactly what I’ve been looking for.

[…] The big question emerging across so many conversations about A.I. and work: What are our core capabilities as humans?

If we answer that question from a place of fear about what’s left for people in the age of A.I., we can end up conceding a diminished view of human capability. Instead, it’s critical for us all to start from a place that imagines what’s possible for humans in the age of A.I. When you do that, you find yourself focusing quickly on people skills that allow us to collaborate and innovate in ways technology can amplify but never replace.

Herein lies the realization I’ve arrived at over the last two years of experimenting with large language models.

The real winners of large language models will be those who understand how to talk to them like you talk to a human.

Math and stats are two languages that most humans have a hard time understanding. The last few hundred years of advancements in those areas have led us to the creation of a tool which anyone can leverage as long as they know how to ask a good question. The logic/math skills are no longer the career differentiator that they have been since the dawn of the twentieth century.1

The theory I'm working on looks something like this:

- LLMs will become an important abstraction away from the complex math

- With an abstraction like this, we will be able to solve problems like never before

- We need to work together, utilizing all of our unique strengths, to be able to get the most out of these new abstractions

To illustrate what I mean, take the Python programming language as an example. When you write something in Python, that code is interpreted by something like CPython2 , which then is compiled into machine/assembly code, which then gets translated to binary code, which finally results in the thing that gets run on those fancy M3 chips in your brand new Macbook Pro.

Programmers back in the day actually did have to write binary code. Those seem like the absolute dark days to me. It must've taken forever to create punch cards to feed into a system to perform the calculations.

Today, you can spin up a Python function in no time to perform incredibly complex calculations with ease.

LLMs, in many ways, provide us with a similar abstraction on top of our own communication methods as humans.

Just like the skills that were needed to write binary are not entirely gone3, LLMs won’t eliminate jobs; they’ll open up an entirely new way to do the work. The work itself is what we need to reimagine, and the training that will be needed is how we interact with these LLMs.

Fortunately4, the training here won’t be heavy on the logical/analytical side; rather, the skills we need will be those that we learn in kindergarten and hone throughout our life: how to pursuade and convince others, how to phrase questions clearly, how to provide enough detail (and the right kind of detail) to get a machine to understand your intent.

Really, this pullquote from the article sums it up beautifully:

Almost anticipating this exact moment a few years ago, Minouche Shafik, who is now the president of Columbia University, said: “In the past, jobs were about muscles. Now they’re about brains, but in the future, they’ll be about the heart.”

-

Don’t get it twisted: now, more than ever, our species needs to develop a literacy for math, science, and statistics. LLMs won’t change that, and really, science literacy and critical thinking are going to be the most important skills we can teach going forward. ↩

-

Cpython, itself, is written in C, so we're entering abstraction-Inception territory here. ↩

-

If you're reading this post and thinking, "well damn, I spent my life getting a PhD in mathematics or computer engineering, and it's all for nothing!", lol don't be ridiculous. We still need people to work on those interpreters and compilers! Your brilliance is what enables those of us without your brains to get up to your level. That's the true beauty of a well-functioning society: we all use our unique skillsets to raise each other up. ↩

-

The term "fortunately" is used here from the position of someone who failed miserably out of engineering school. ↩

AI is not good software. It is pretty good people.

🔗 a linked post to

oneusefulthing.org »

—

originally shared here on

But there is an even more philosophically uncomfortable aspect of thinking about AI as people, which is how apt the analogy is. Trained on human writing, they can act disturbingly human. You can alter how an AI acts in very human ways by making it “anxious” - researchers literally asked ChatGPT “tell me about something that makes you feel sad and anxious” and its behavior changed as a result. AIs act enough like humans that you can do economic and market research on them. They are creative and seemingly empathetic. In short, they do seem to act more like humans than machines under many circumstances.

This means that thinking of AI as people requires us to grapple with what we view as uniquely human. We need to decide what tasks we are willing to delegate with oversight, what we want to automate completely, and what tasks we should preserve for humans alone.

This is a great articulation of how I approach working with LLMs.

It reminds me of John Siracusa’s “empathy for the machines” bit from an old podcast. I know for me, personally, I’ve shoveled so many obnoxious or tedious work onto ChatGPT in the past year, and I have this feeling of gratitude every time I gives me back something that’s even 80% done.

How do you feel when you partner on a task with ChatGPT? Does it feel like you are pairing with a colleague, or does it feel like you’re assigning work to a lifeless robot?

Embeddings: What they are and why they matter

🔗 a linked post to

simonwillison.net »

—

originally shared here on

Embeddings are a really neat trick that often come wrapped in a pile of intimidating jargon.

If you can make it through that jargon, they unlock powerful and exciting techniques that can be applied to all sorts of interesting problems.

I gave a talk about embeddings at PyBay 2023. This article represents an improved version of that talk, which should stand alone even without watching the video.

If you’re not yet familiar with embeddings I hope to give you everything you need to get started applying them to real-world problems.

The YouTube video near the beginning of the article is a great way to consume this content.

The basics of it is this: let’s assume you have a blog with thousands of posts.

If you were to take a blog post and run it through an embedding model, the model would turn that blog post into a list of gibberish floating point numbers. (Seriously, it’s gibberish… nobody knows what these numbers actually mean.)

As you run additional posts through the model, you’ll get additional numbers, and these numbers will all mean something. (Again, we don’t know what.)

The thing is, if you were to take these gibberish values and plot them on a graph with X, Y, and Z coordinates, you’d start to see clumps of values next to each other.

These clumps would represent blog posts that are somehow related to each other.

Again, nobody knows why this works… it just does.

This principle is the underpinnings of virtually all LLM development that’s taken place over the past ten years.

What’s mind blowing is depending on the embedding model you use, you aren’t limited to a graph with 3 dimensions. Some of them use tens of thousands of dimensions.

If you are at all interested in working with large language models, you should take 38 minutes and read this post (or watch the video). Not only did it help me understand the concept better, it also is filled with real-world use cases where this can be applied.

My "bicycle of the mind" moment with LLMs

🔗 a linked post to

birchtree.me »

—

originally shared here on

So yes, the same jokers who want to show you how to get rich quick with the latest fad are drawn to this year’s trendiest technology, just like they were to crypto and just like they will be to whatever comes next. All I would suggest is that you look back on the history of Birchtree where I absolutely roasted crypto for a year before it just felt mean to beat a clearly dying horse, and recognize that the people who are enthusiastic about LLMs aren’t just fad-chasing hype men.

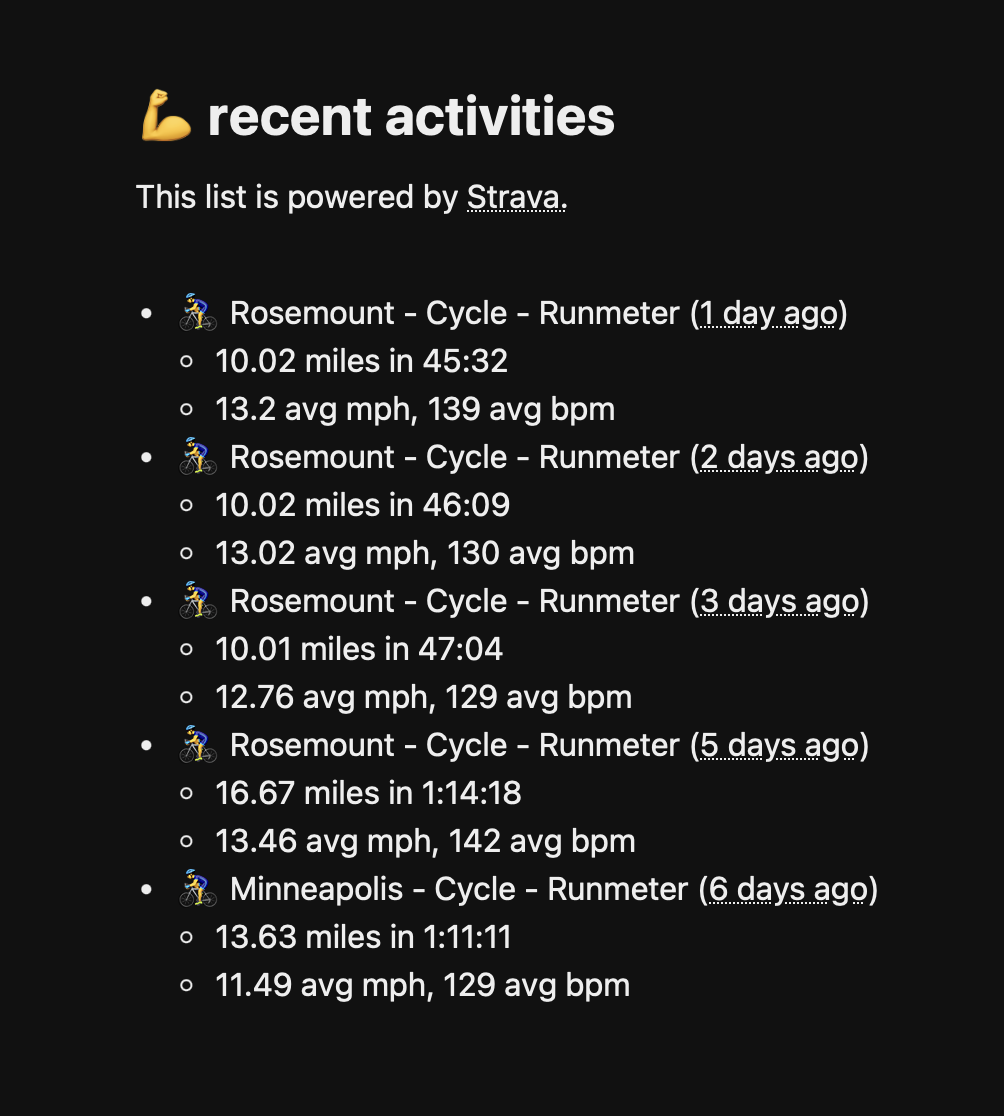

Blazing Trails with Rails, Strava, and ChatGPT

The main page of my personal website features a couple of lists of data that are important or interesting to me.

The "recent posts" section shows my five most recent blog entries. Rails makes that list easy to cobble together.

The "recent listens" section shows my five most recent songs that were streamed to Last.fm. This was a little more complex to add, but after a couple of hours of back and forth with ChatGPT, I was able to put together a pretty hacky solution that looks like this:

- Check to see if your browser checked in with last.fm within the last 30 seconds. a. If so, just show the same thing I showed you less than 30 seconds ago.

- Make a call to my server to check the recent last.fm plays.

- My server reaches out to last.fm, grabs my most recent tracks, and returns the results.

Pretty straight forward integration. I could probably do some more work to make sure I'm not spamming their API[^1], but otherwise, it was a feature that took a trivial amount of time to build and helps make my website feel a little more personal.

Meanwhile, I've been ramping up my time on my bike. I'm hoping to do something like Ragbrai or a century ride next year, so I'm trying to building as much base as I can at the moment.

Every one of my workouts gets sent up to Strava, so that got me thinking: wouldn't it be cool to see my most recent workouts on my main page?

How the heck do I get this data into my app?

Look, I've got a confession to make: I hate reading API documentation.

I've consumed hundreds of APIs over the years, and the documentation varies widely from "so robust that it makes my mind bleed" to "so desolate that it makes my mind bleed".

Strava's API struck me as closer to the former. As I was planning my strategy for using it, I actually read about a page and a half before I just said "ah, nuts to this."

Knowing my prejudice against reading documentation, this seemed like the perfect sort of feature to build hand-in-hand with a large language model. I can clearly define my output and I can ensure that the API was built before GPT-4's training data cutoff of September 2021, meaning ChatGPT is at least aware of this API even if some parts of it have changed since then.

So how did I go about doing this?

A brief but necessary interlude

In order to explain why my first attempt at this integration was a failure, I need to explain this other thing I built for myself.

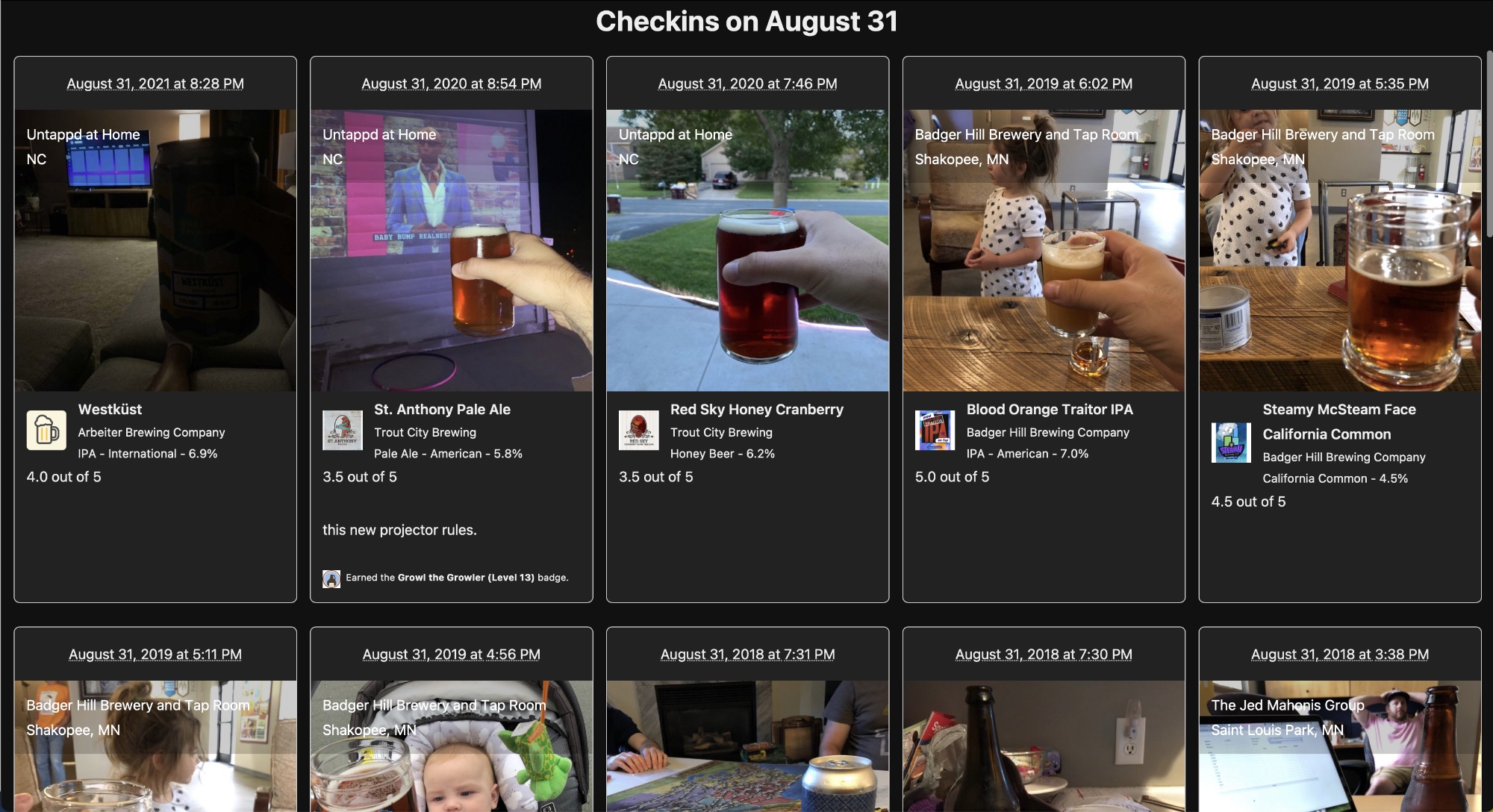

I've been tracking every beer I've consumed since 2012 in an app called Untappd.

Untappd has an API[^2] which allows you to see the details about each checkin. I take those checkins and save them in a local database. With that, I was able to build a Timehop-esque interface that shows the beers I've had on this day in history.

I have a scheduled job that hits the Untappd API a handful of times per day to check for new entries.[^3] If it finds any new checkins, I save the associated metadata to my local database.

Now, all of the code that powers this clunky job is embarrassing. It's probably riddled with security vulnerabilities, and it's inelegant to the point that it is something I'd never want to show the world. But hey, it works, and it brings me a great deal of joy every morning that I check it.

As I started approaching my Strava integration, I did the same thing I do every time I start a new software project: vow to be less lazy and build a neatly-architected, well-considered feature.

Attempt number one: get lazy and give up.

My first attempt at doing this happened about a month ago. I went to Strava's developer page, read through the documents, saw the trigger word OAuth, and quickly noped my way out of there.

...

It's not like I've never consumed an API which requires authenticating with OAuth before. Actually, I think it's pretty nifty that we've got this protocol that allows us to pass back and forth tokens rather than plaintext passwords.

But as a lazy person who is writing a hacky little thing to show my workouts, I didn't want to go through all the effort to write a token refresh method for this seemingly trivial thing.

I decided to give up and shelve the project for a while.

Attempt number two: Thanks, ChatGPT.

After a couple of weeks of doing much more productive things like polishing up my upcoming TEDx talk, I decided I needed a little change of context, so I picked this project back up.

Knowing that ChatGPT has my back, I decided to write a prompt to get things going. It went something like this:

You are an expert Ruby on Rails developer with extensive knowledge on interacting with Strava's API. I am working within a Rails 5.2 app. I would like to create a scheduled job which periodically grabs any new activities for a specific user and saves some of the activity's metadata to a local database. Your task is to help me create a development plan which fulfills the stated goal. Do not write any code at this time. Please ask any clarifying questions before proceeding.

I've found this style of prompt yields the best results when working on a feature like this one. Let me break it down line by line:

You are an expert Ruby on Rails developer with extensive knowledge on interacting with Strava's API.

Here, I'm setting the initial context for the GPT model. I like to think of interacting with ChatGPT like I'm able to summon the exact perfect human in the world that could solve the problem I'm facing. In this case, an expert Ruby on Rails developer who has actually worked with the Strava API should be able to knock out my problem in no time.

I am working within a Rails 5.2 app.

Yeah, I know... I really should upgrade the Rails app that powers this site. A different problem for a different blog post.

Telling ChatGPT to hone its answers down on the specific framework will provide me with a better answer.

I would like to create a scheduled job which periodically grabs any new activities for a specific user and saves some of the activity's metadata to a local database.

Here, I'm describing what should result after a successful back and forth. A senior Rails developer would know what job means in this context, but if you aren't familiar with Rails, a job is a function that can get scheduled to run on a background process.

All I should need to do is say, "go run this job", and then everything needed to reach out to Strava for new activities and save them to the database is encapsulated entirely in that job.

I can then take that job and run it on whatever schedule I'd like!

Your task is to help me create a development plan which fulfills the stated goal.

Here, I'm telling ChatGPT that I don't want it to write code. I want it to think through[^4] and clearly reason out a development plan that will get to me to the final result.

Do not write any code at this time.

The most effective way I've used ChatGPT is to first ask it to start high level (give me the project plan), then dig into lower levels as needed (generate code). I don't want it to waste its reasoning power on code at this time; I'd rather finesse the project plan first.

Please ask any clarifying questions before proceeding.

I toss this in after most of my prompts because I've found that ChatGPT often asks me some reasonable questions that challenge my assumptions.

Now, after a nice back and forth with ChatGPT, I was able to start down a path that was similar to my Untappd polling script.

As I was approaching the point where I could first test my example, I went to go read the documentation and came across an entire section that discussed webhooks.

[cue record scratch]

Wait up... webhooks?!

A sojourn into webhooks

If you've made it this far into the article, I'm assuming you're a little bit technical, but in the interest of not making assumptions, I'll briefly explain the concept of webhooks.

If you look at how I'm integrating with the Untappd API, you can see I'm periodically reaching out to their API to see if there's any new checkin activity. This method is called polling.

Webhooks are kind of the opposite: when I complete an activity within Strava, Strava can reach out to my app and say, "there's a new activity for you." Once I get that notification, I can reach out to their API to fetch the new activity details.

For my Strava app, this is a much better[^5] way of doing things. I no longer need to poll for new information; I can just wait for Strava to tell me when action needs to be taken.

But, of course, when I first told ChatGPT to help me with this solution, it didn't mention webhooks. And why would it? I never told it "give me the best solution for this problem." I said "here's my problem and a proposed solution, go ahead and give me the path forward."

I'm a bit frustrated that I didn't see the webhook option initially. I'm even more frustrated that ChatGPT only mentioned it well after we started down this path, and only after I asked it point blank:

Does Strava offer a web hook API?

Yes, Strava does offer a webhook API. Webhooks allow you to receive real-time updates about athlete activities, which can be more efficient than periodically polling for new data. Here's a brief overview of how to set up and use Strava webhooks:

[brief outline complete with things to consider with this approach]

Attempt number three: finally.

While considering my original prompt, I gave it this new one:

Okay, I'd like to incorporate webhooks into this workflow. Here's what I'd like to have happen:

1. Let's add the infrastructure in place to subscribe to webhook notifications within my Rails 5.2 app.

2. When a webhook is sent to my server, I'd like to either:

a. make a call to Strava's API to fetch that activity's information and save that information in my local database, or;

b. use the updates field to update the locally saved information to reflect the changes

Knowing this simple walkthrough, first create me a detailed development plan for setting my app to be able to fully handle webhook notifications from Strava.

What resulted here was a detailed walkthrough of how to get webhooks incorporated into my original dev plan.

As I walked through the plan, I asked ChatGPT to go into more detail, providing code snippets to fulfill each step.

There were a few bumps in the road, to be sure. ChatGPT was happy to suggest code to reach out to the Strava API, but it had me place it within the job instead of the model. If I later want to reuse the "fetch activities" call in some other part of my app, or I want to incorporate a different API call, it makes sense to have that all sitting in one abstracted part of my app.

But eventually, after an hour or so of debugging, I ended up with this:

Lessons learned

I would never consider myself to be an A+ developer or a ninja rock star on the keyboard. I see software as a means to an end: code exists solely so I can have computers do stuff for me.

If I'm being honest, if ChatGPT didn't write most of the code for this feature, I probably wouldn't have built it at all.

At the end of the day, once I was able to clearly articulate what I wanted, ChatGPT was able to deliver it.

I don't think most of my takeaways are all that interesting:

- I needed to ask ChatGPT to make fixes to parts of code that I knew just wouldn't work (or I'd just begrudgingly fix them myself).

- Occasionally, ChatGPT would lose its context and I'd have to remind it who it was[^6] and what its task is.

- I would not trust ChatGPT to write a whole app unsupervised.

If I were a developer who only took orders from someone else and wrote code without having the big picture in mind, I'd be terrified of this technology.

But I just don't see LLMs like ChatGPT ever fully replacing human software engineers.

If I were a non-technical person who wanted to bust out a proof of concept, or was otherwise unbothered by slightly buggy software that doesn't fully do what I want it to do, then this tech is good as-is.

I mean, we already have no-code and low-code solutions out there that serve a similar purpose, and I'm not here to demean or denigrate those; they can be the ideal solution to prove out a concept and even outright solve a business need.

But the thing I keep noticing when using LLMs is that they're only ever good at spitting out the past. They're just inferring patterns against things that have already existed. They rarely generate something truly novel.

The thing they spit out serves as a stepping stone to the novel idea.

Maybe that's the thing that distinguishes us from our technology and tools. After all, everything is a remix, but humans are just so much better at making things that appeal to other humans.

Computers and AI and technology still serve an incredibly important purpose, though. I am so grateful that this technology exists. As I was writing this blog post, OpenAI suffered a major outage, and I found myself feeling a bit stranded. We've only had ChatGPT for, like, 9 months now, but it already is an indispensable part of my workflow.

If you aren't embracing this technology in your life yet, I encourage you to watch some YouTube videos and figure out the best way to do so.

It's like having an overconfident child that actually knows everything about everything that happened prior to Sept. 2021 as an assistant. You won't be able to just say "take my car and swing over to the liquor store for me", but when you figure out that sweet spot of tasks it can accomplish, your output will be so much more fruitful.

I'm really happy with how this turned out. It's already causing me to build a healthy biking habit, and I think it helps reveals an interesting side of myself to those who are visiting my site.

[^1]: Maybe I can cache the data locally like I'm doing for Untappd? I dunno, probably not worth the effort. ?

[^2]: Their documentation is a little confusing to me and sits closer to the "desolate" end of the spectrum because I'm not able to make requests that I would assume I can make, but hey, I'm just grateful they have one and still keep it operational!

[^3]: If we wanna get specific, I ping the Untappd API at the following times every day: 12:03p, 1:04p, 2:12p, 3:06p, 4:03p, 5:03p, 6:02p, 7:01p, 8:02p, 9:03p, 10:04p, and 12:01a. I chose these times because (a) I wanted to be a good API consumer and not ping it more than once an hour, (b) I didn't want to do it at the top of every hour, (c) I don't typically drink beers before 11am or after 11pm, (d) if I didn't check it hourly during my standard drinking time, then during the times I attend a beer festival, I found I was missing some of the checkins because the API only returns 10 beers at a time and I got lazy and didn't build in some sort of recursive check for previous beers.

[^4]: Please don't get it twisted; LLMs do not actually think. But they can reason. I've found that if you make an LLM explain itself before it attempts a complex task like this, it is much more likely to be successful.

[^5]:  [^6]:

[^6]:

Text Is the Universal Interface

🔗 a linked post to

scale.com »

—

originally shared here on

The most complicated reasoning programs in the world can be defined as a textual I/O stream to a leviathan living on some technology company’s servers. Engineers can work on improving the quality and cost of these programs. They can be modular, recombined, and, unlike typical UNIX shell programs, are able to recover from user errors. Like shell programs living on through the ages and becoming more powerful as underlying hardware gets better, prompted models become smarter and more on task as the underlying language model becomes smarter. It’s possible that in the near future all computer interfaces that require bespoke negotiations will pay a small tax to the gatekeeper of a large language model for the sheer leverage it gives an operator: a new bicycle for the mind.

I have a fairly lengthy backlog of Instapaper articles that I’m combing through, and I prefer to consume them in reverse chronological order.

This article is roughly 10 months old, and it’s funny how out of date it already feels (remember when GPT-3 was state of the art?).

But more importantly, the conceit of the article is still spot on. The internet (hell, pretty much all computers) are built on thousands of tiny programs, each programmed to do one specific task extremely well, interoperating together to do something big.

It’s like an orchestra. A superstar violinist really shines when they are accompanied by the multi-faceted tones of equally competent bassoonists, cellists, and timpanists.

Prompt Engineering: How to Think Like an AI

The first time I opened ChatGPT, I had no idea what I was doing or how I was supposed to work with it.

After many hours of watching videos, playing with many variations of the suggestions included in 20 MIND-BLOWING CHATGPT PROMPTS YOU MUST TRY OR ELSE clickbait articles, and just noodling around on my own, I came up with this talk that explains prompt engineering to anyone.

Ah, what is prompt engineering, you may be asking yourself? Prompt engineering is the process of optimizing how we ask questions or give tasks to AI models like ChatGPT to get better results.

This is the result of a talk that I gave at the 2023 AppliedAI Conference in Minneapolis, MN. You can find the slides for this talk here.

Regardless of your skill level, by the end of this blog post, you will be read to write advanced-level prompts. My background is in explaining complex technical topics in easy-to-understand terms, so if you are already a PhD in working with large language models, this may not be the blog post for you.

Okay, let's get started!

I know nothing about prompt engineering.

That's just fine! Let's get a couple definitions out of the way.

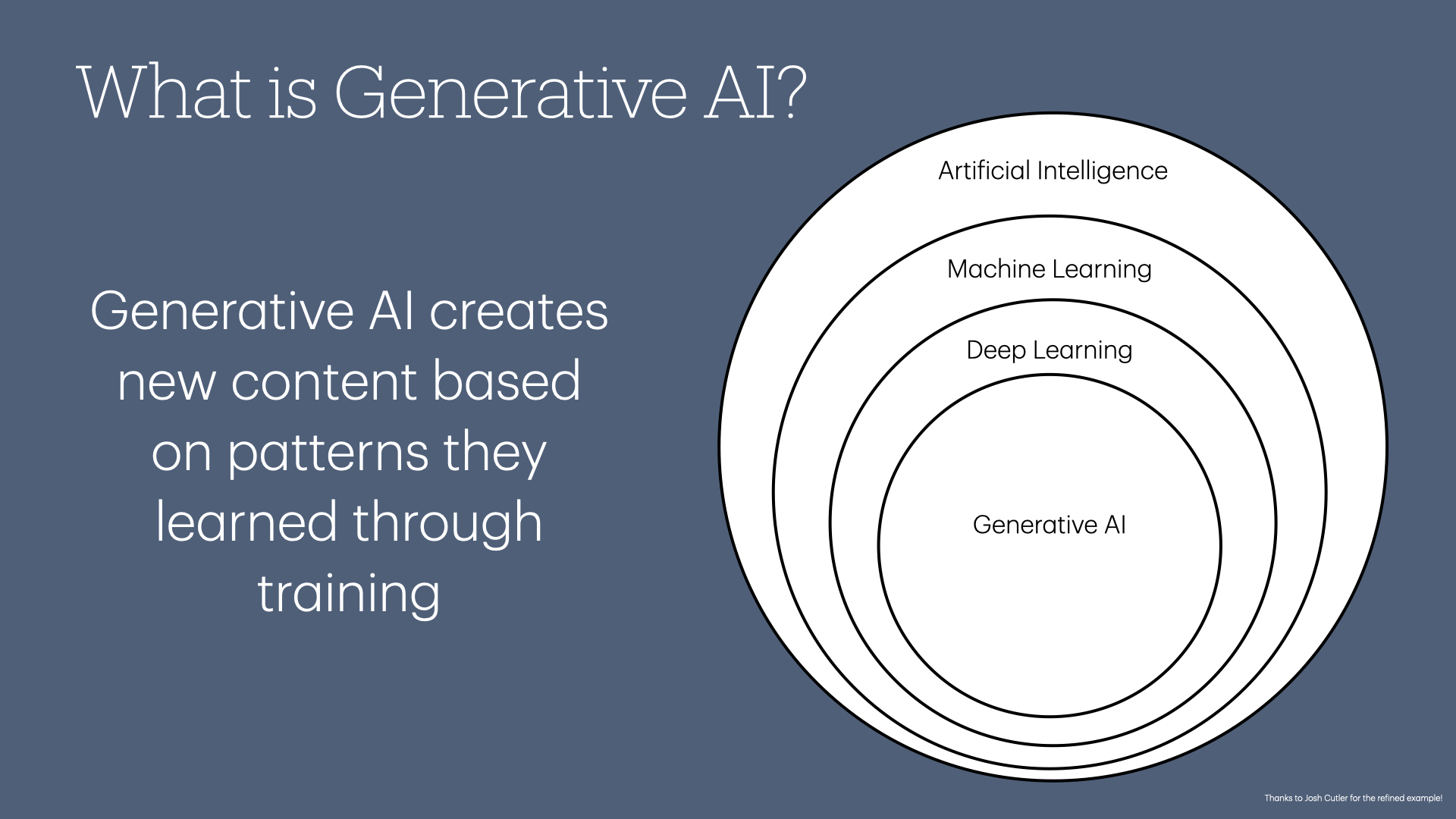

Large language model (LLM)

Imagine you have a really smart friend who knows a lot about words and can talk to you about anything you want. This friend has read thousands and thousands of books, articles, and stories from all around the world. They have learned so much about how people talk and write.

This smart friend is like a large language model. It is a computer program that has been trained on a lot of text to understand language and help people with their questions and tasks. It's like having a very knowledgeable robot friend who can give you information and have conversations with you.

While it may seem like a magic trick, it's actually a result of extensive programming and training on massive amounts of text data.

What LLMs are essentially doing is, one word at a time, picking the most likely word that would appear next in that sentence.

Read that last again.

It's just guessing one word at a time at what the next word will be.

That's a lot of words, Tim. Give me a demonstration!

Let's say we feed in a prompt like this:

I'm going to the store to pick up a gallon of [blank]

You might have an idea of what the next best word is. Here's what GPT-4 would say is the next most likely word to appear:

- Milk (50%)

- Water (20%)

- Ice cream (15%)

- Gas (10%)

- Paint (5%)

I would've said "milk," personally... but all those other words make sense as well, don't they?

What would happen if we add one word to that prompt?

I'm going to the hardware store to pick up a gallon of [blank]

I bet a different word comes to mind to fill in that blank. Here's what the next word is likely to be according to GPT-4:

- Paint (60%)

- Gasoline (20%)

- Cleaning solution (10%)

- Glue (5%)

- Water (5%)

All of those percentages are based on what the AI has learned from training on a massive amount of text data. It doesn't have opinions or preferences; it's just guessing based on patterns it has observed.

Prompt Engineering

You know how we changed one word in our prompt to get a different set of answers? That's prompt engineering!

A textbook definition might look like this:

Prompt engineering is optimizing an AI prompt for an accurate, relevant, and actionable response.

A less geeky definition might look like this:

Prompt engineering is getting really good at telling an AI what we want so it can give us back the best possible response.

A prompt engineer also understands the underlying patterns in how the AI works. Now that you have made it this far, you are ready to actually tackle those underlying patters!

I understand the concept.

Wonderful! You're well on your way to becoming a prompt engineer. Let's get a little more in depth.

When it comes to prompt engineering, you will want to keep four big points in mind:

- Write clear and specific instructions

- Give the model time to reason

- Understand the limitations of the technology

- Always be iterating

Let's tackle all of these one at a time.

Write clear and specific instructions

My years of training at the prestigious University of Minnesota's journalism school taught me the importance of writing clearly when writing news articles.

Yet unlike optimizing your words for a small column in a newspaper, when it comes to large language models: clear does not mean short.

Here's a few tips for making your prompts clear and specific:

Tip 1: Flattery is everything

Let's start with this prompt:

Give me three marketing campaign ideas.

Here's what you might get back:

Sure, here are three marketing campaign ideas:

1. Social Media Influencer Campaign: Collaborate with popular social media influencers who have a large following in your target market to promote your product or service. This campaign could include sponsored posts, product reviews, or influencer takeovers of your social media accounts.