The most compelling use case I see for agentic programming is to enable home-cooked software on a scale like never before. As part of my burnout recovery, I noticed that I've been searching for years for a home-cooked meal I can sink my teeth into and build for myself.

I recently beta tested James Reeves' Spite. It's an exceptional, opinionated music player, targeted to fit James' vision for how he consumes music.

As I was playing around with it, it dawned on me: I could do this.

I have opinions. I have $20 per month. I have a decade of iOS development experience.

So I've decided I'm going to see how far I can push an agent to help me brew up a custom music player.

I'm calling it Lunara.

My requirements

I currently use Plexamp to achieve about 90% of what I would like to do with my music listening... but it's that 10% that I'm going to push on to see how weird I can make this app.

I want to build this in public.

I want to mostly use agentic tools. I'll drop into Xcode and help handle some of the quirks that LLMs can't handle yet, but for the most part, I'm gonna be hands off of the code itself. I will be more concerned about writing clear requirements up front, reviewing the unit tests that the agents will write, and dogfood the hell out of it.

The app will evolve to match my specific listening habits. As I outline in the project readme, I use Plex to manage my library. I've spent an embarrassing amount of time pruning my library, adding tags and high res album art and whatnot. I don't want to replace it; I want a new front end that integrates deeply with it.

I see my digital music garden as a large pool. I like to jump into my library and wade around, often hitting "shuffle" on my thousands of songs until something matches my current mood.

I never plan on releasing this thing to the App Store, by the way. If you want, you can absolutely download the repo and run it against your own Plex library. In fact, one of the dopest things that the agents have done so far is incorporate Plex's PIN login approach. I have a feeling I'll say this a lot, but I absolutely would not have gone that far had I been forced to write all of this myself.

Current progress

I've been obsessed with this idea for the last 24 hours. And in just 24 hours, I've been truly unbelievable progress.

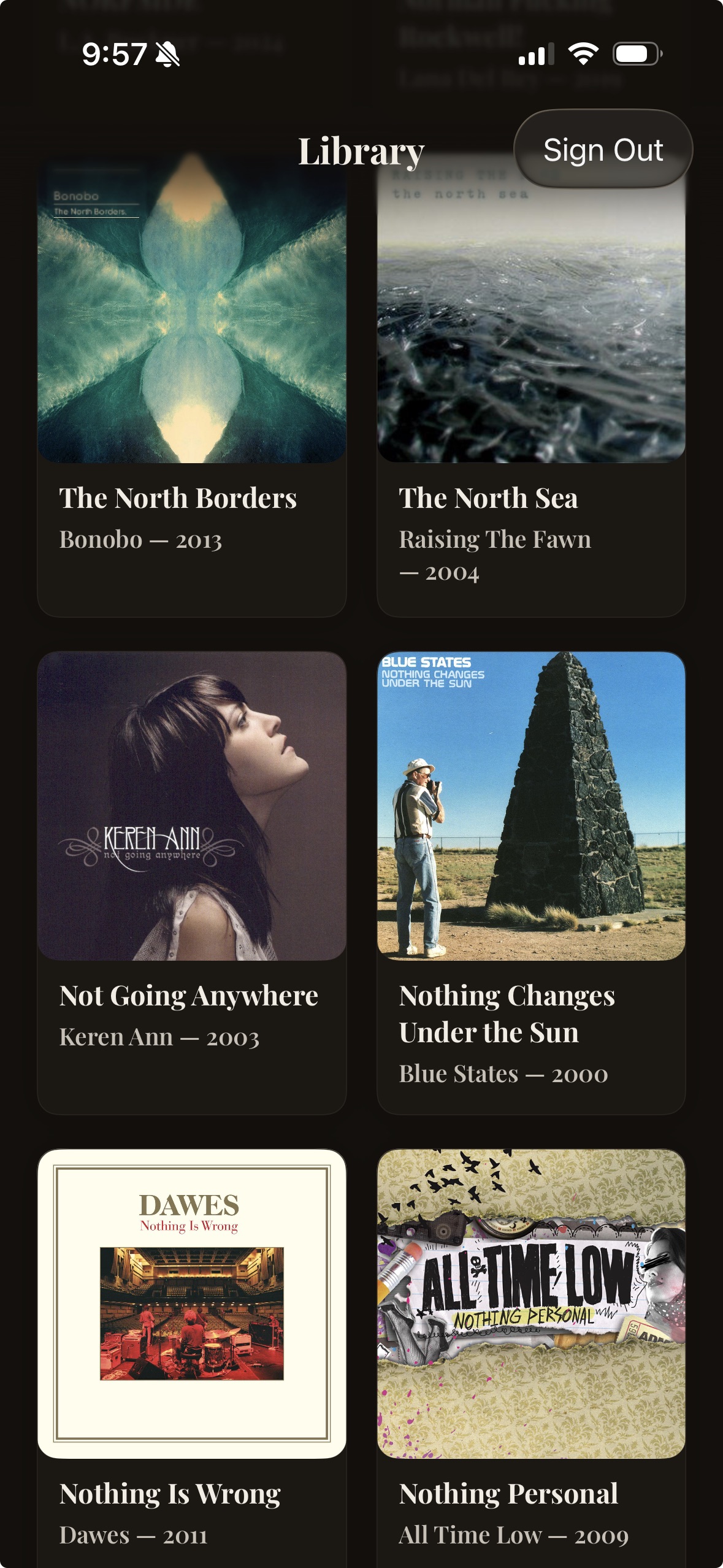

Using gpt-5.2-codex-medium with the Codex app for macOS (since it gives me 2x tokens lol), here are a couple screenshots of what I've built:

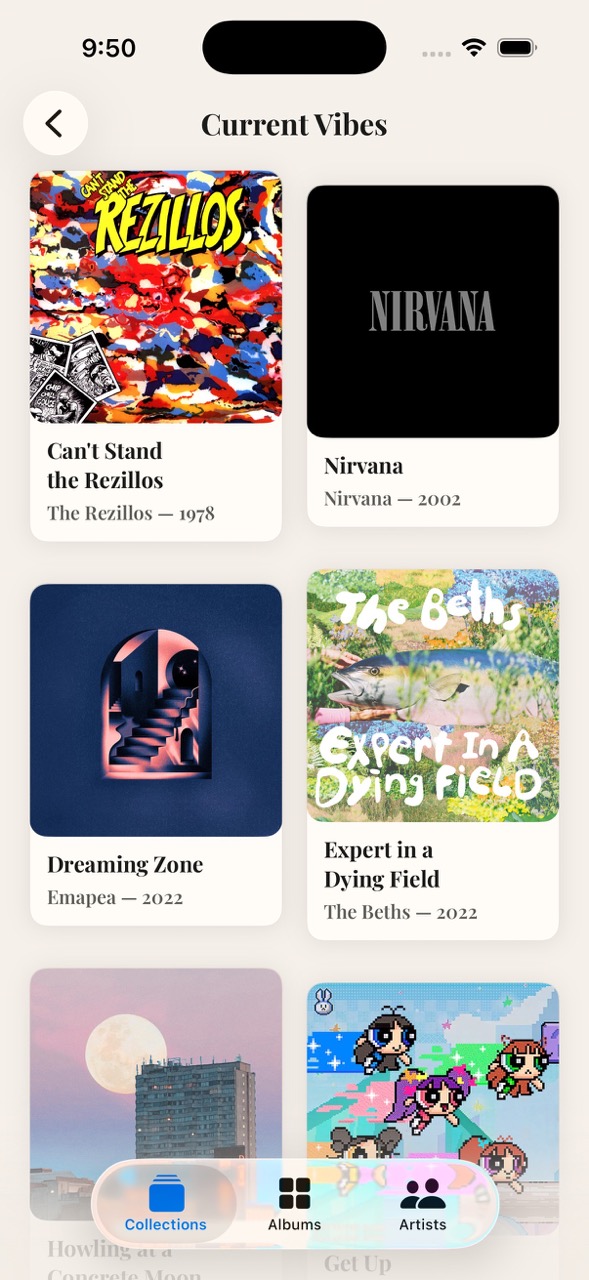

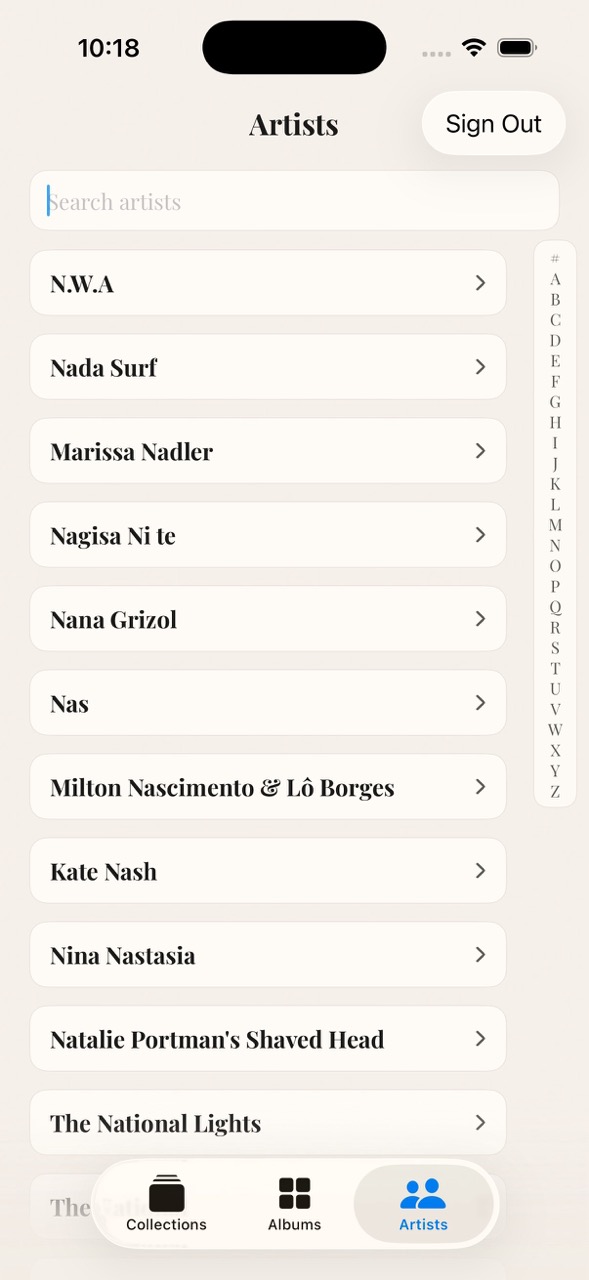

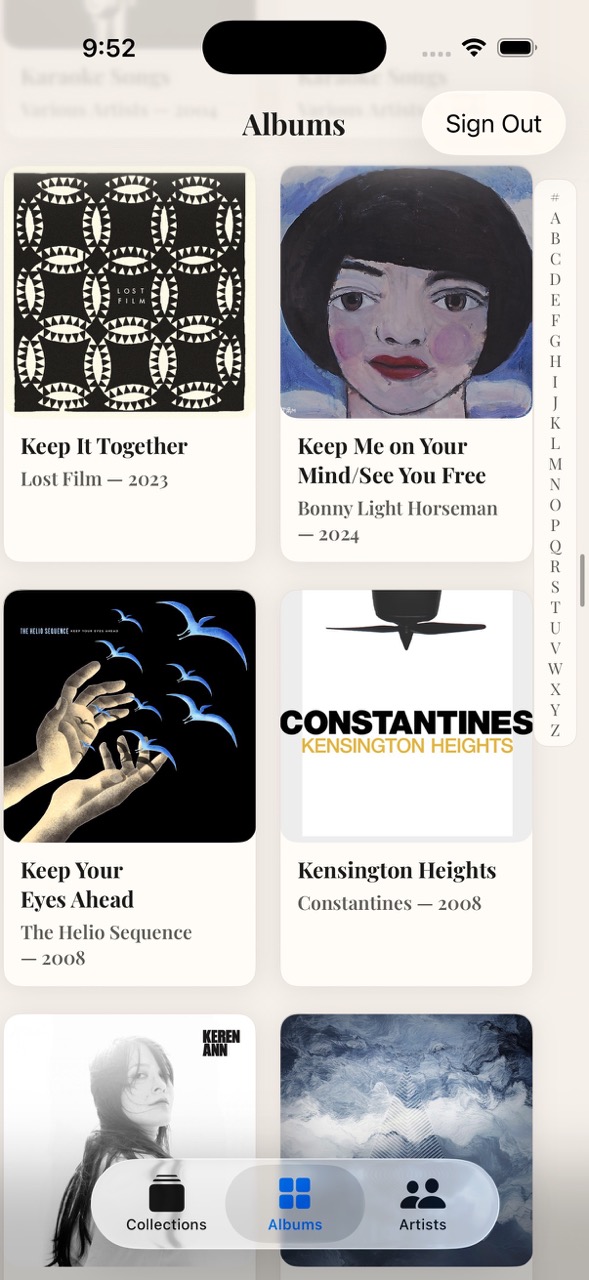

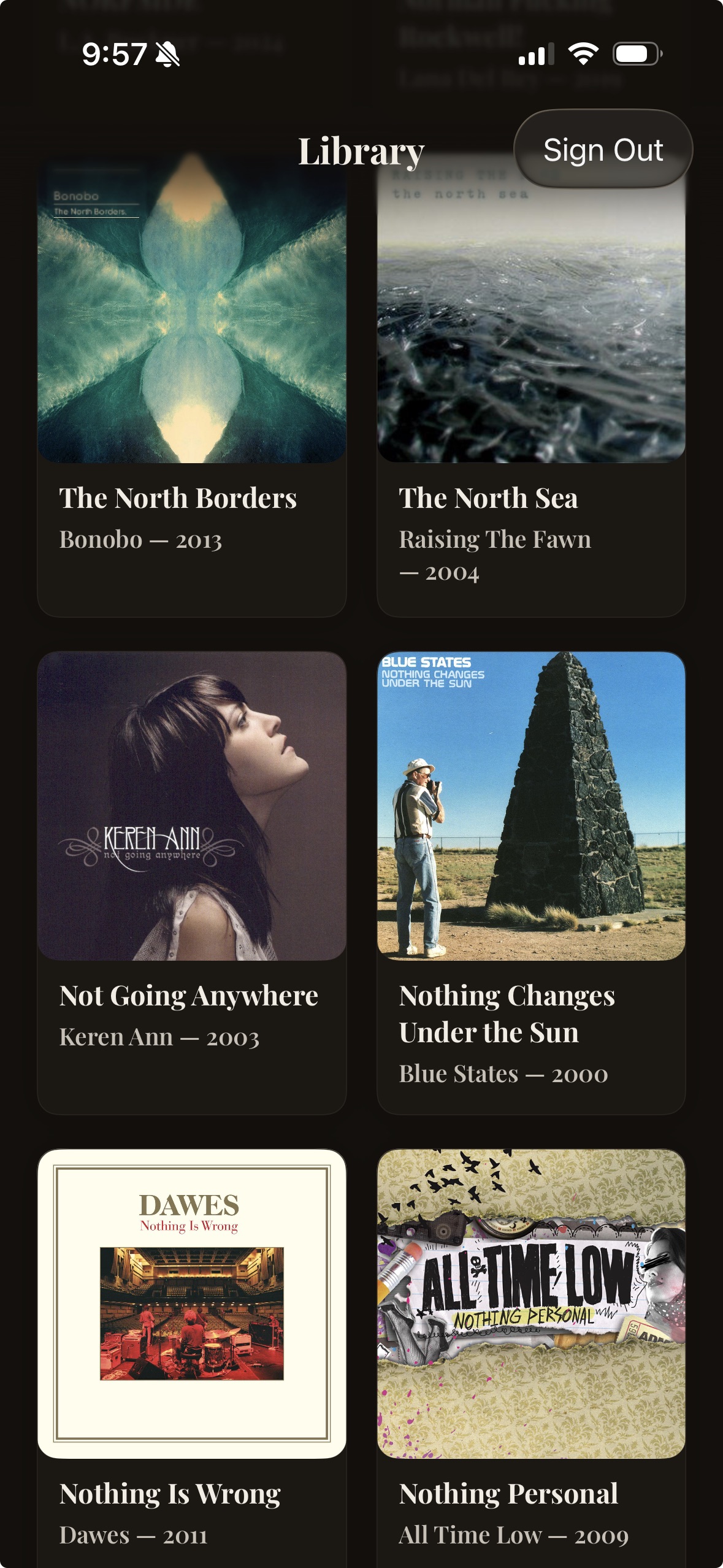

This is the main page so far. It's a grid of album art. It's not very impressive, except for the fact that it's loading dynamically from an authenticated Plex session and none of this existed 24 hours ago.

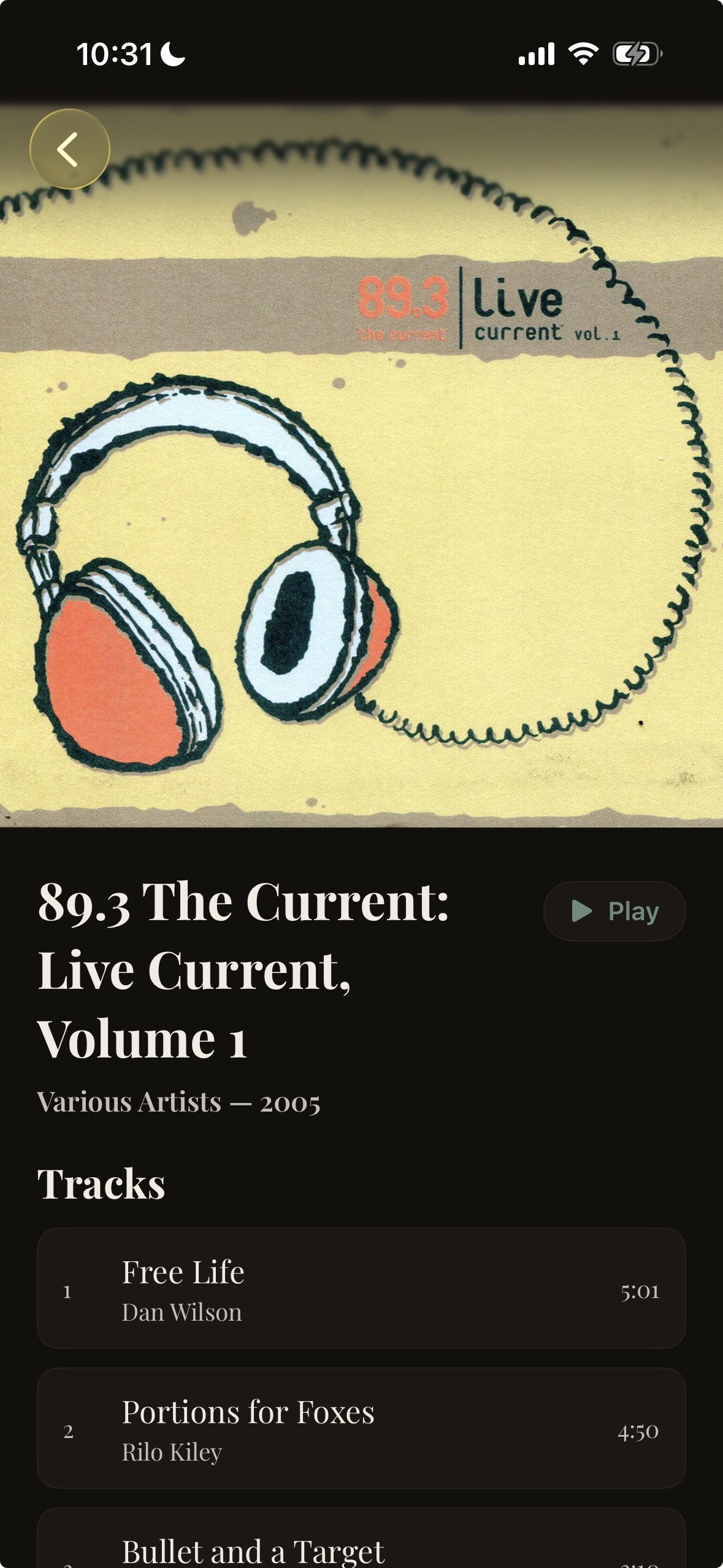

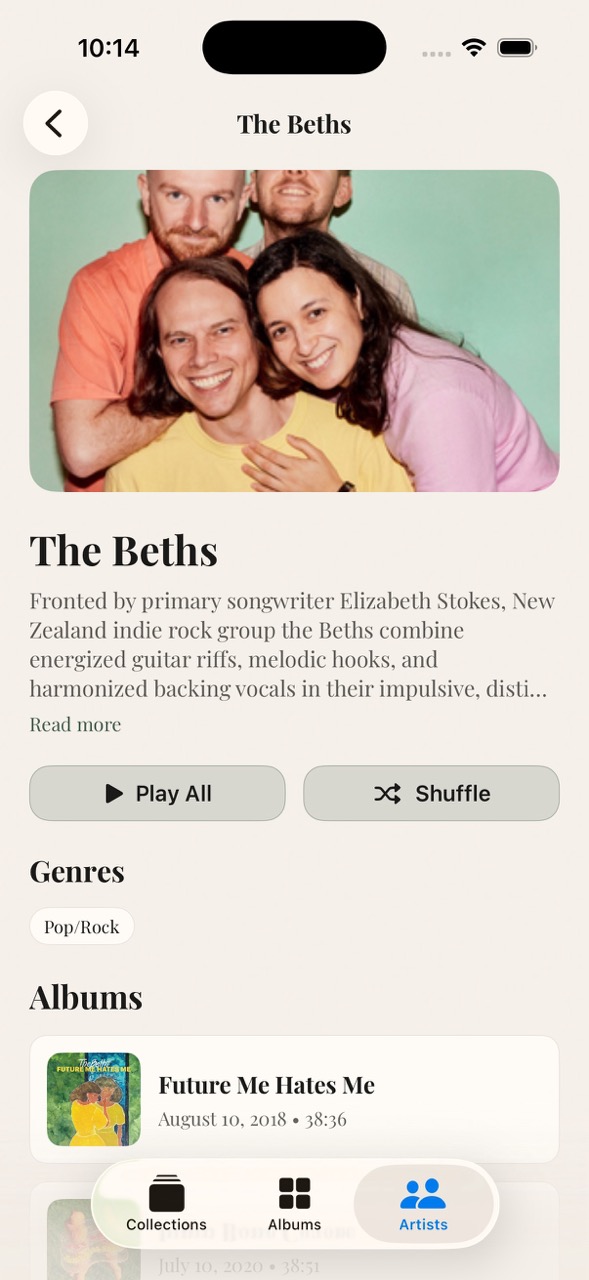

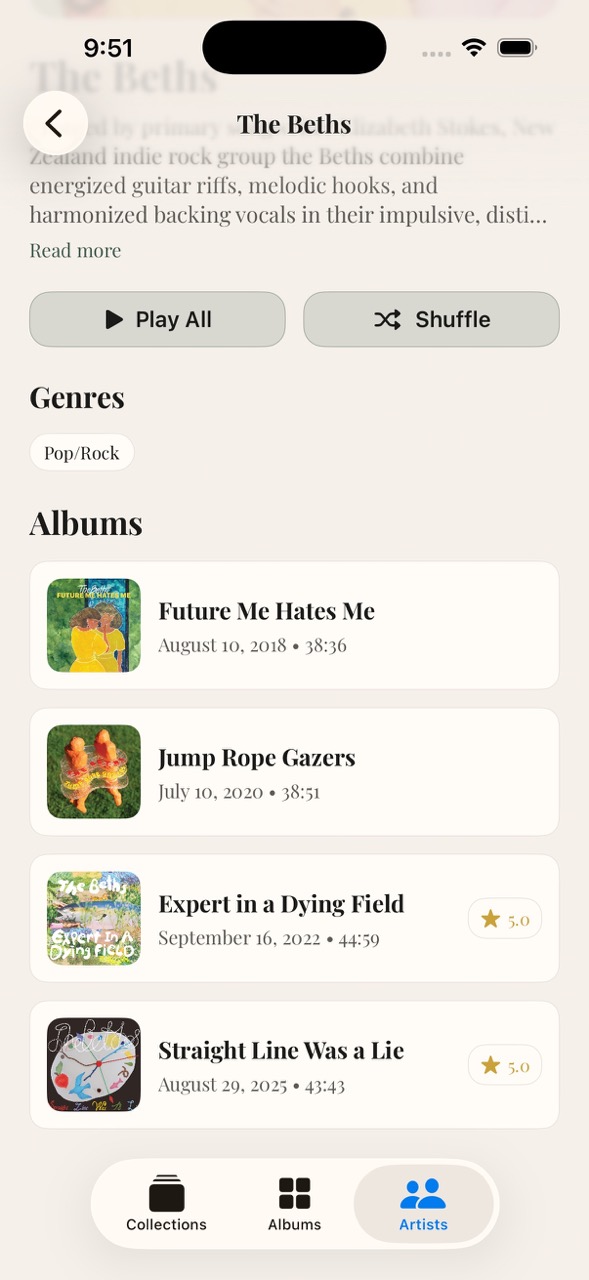

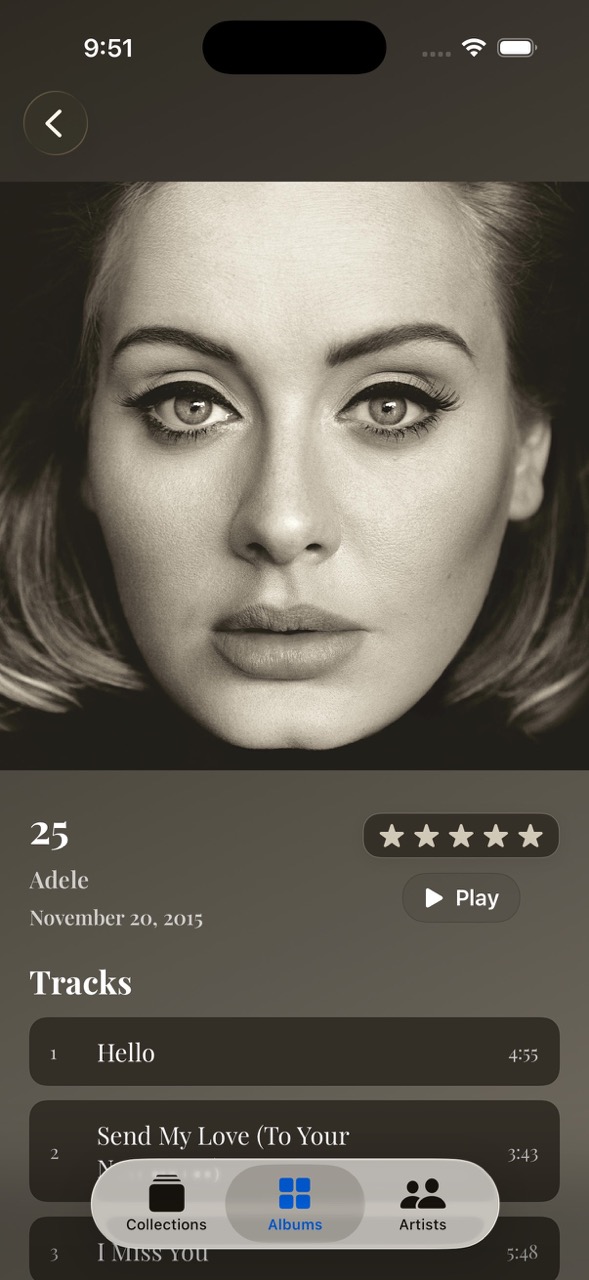

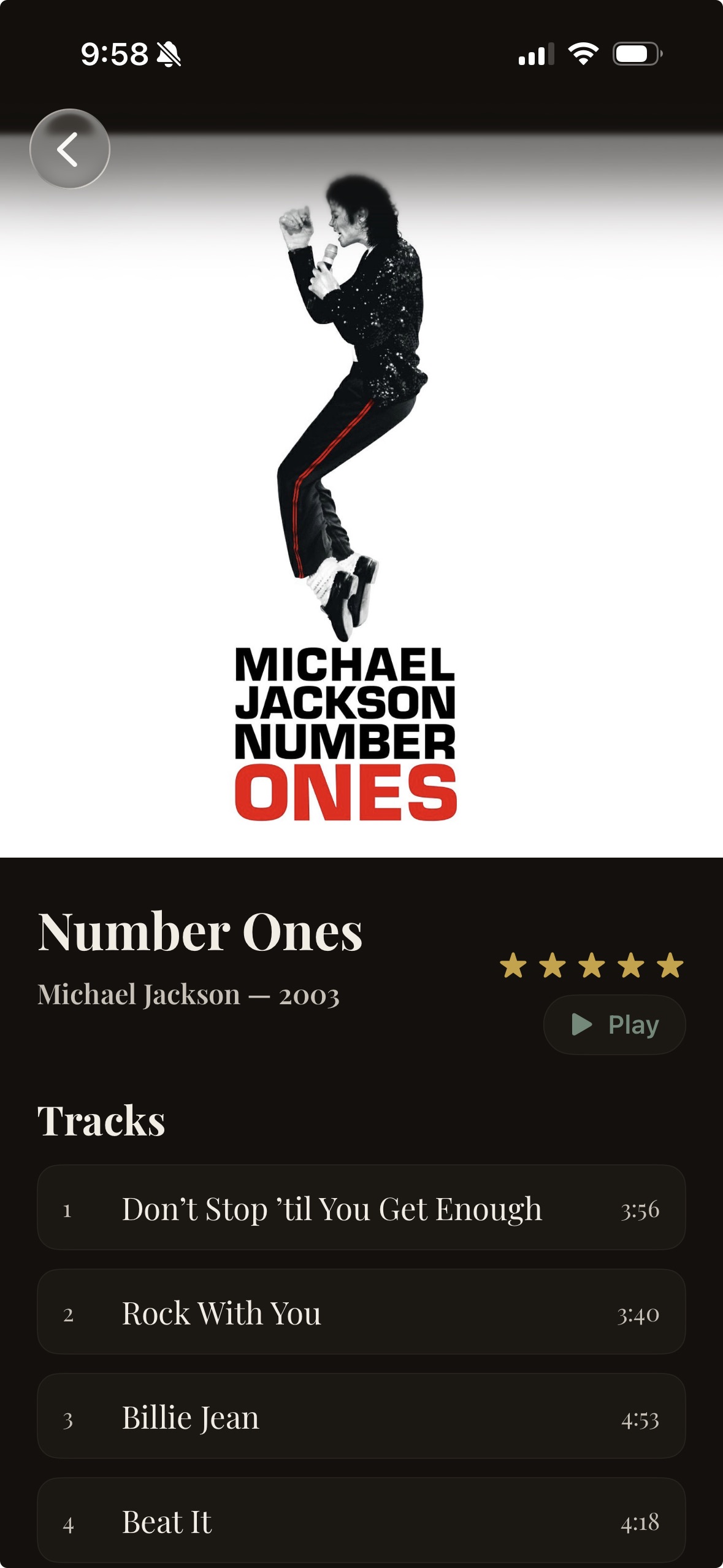

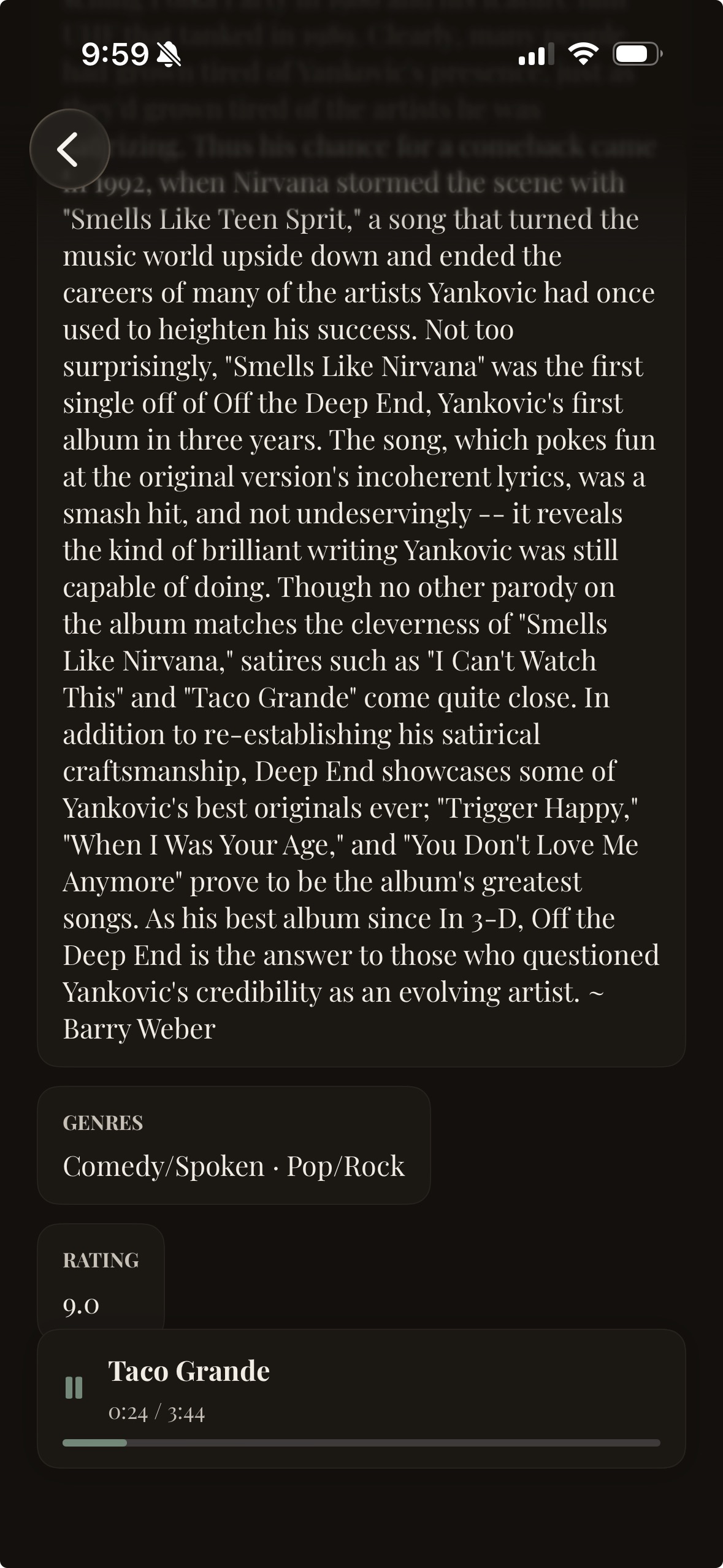

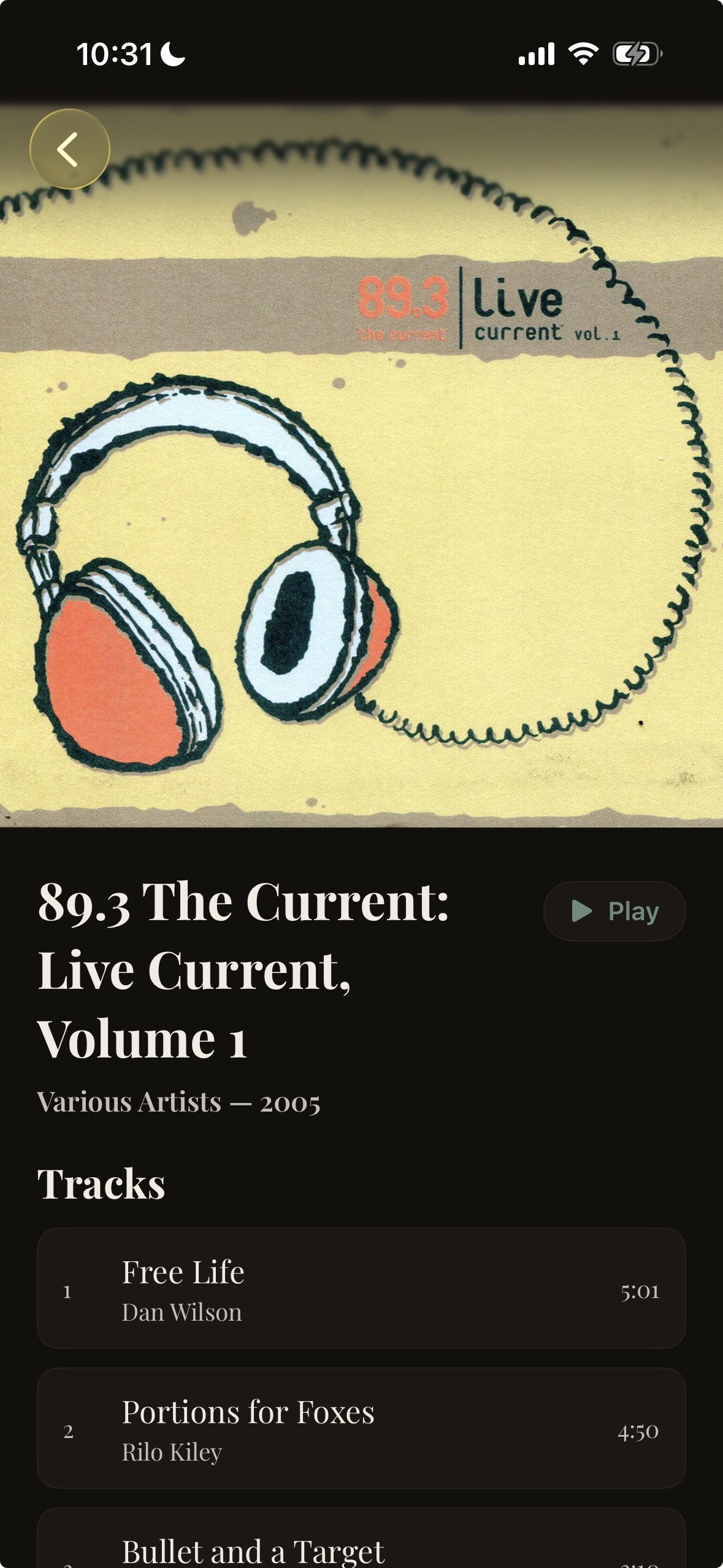

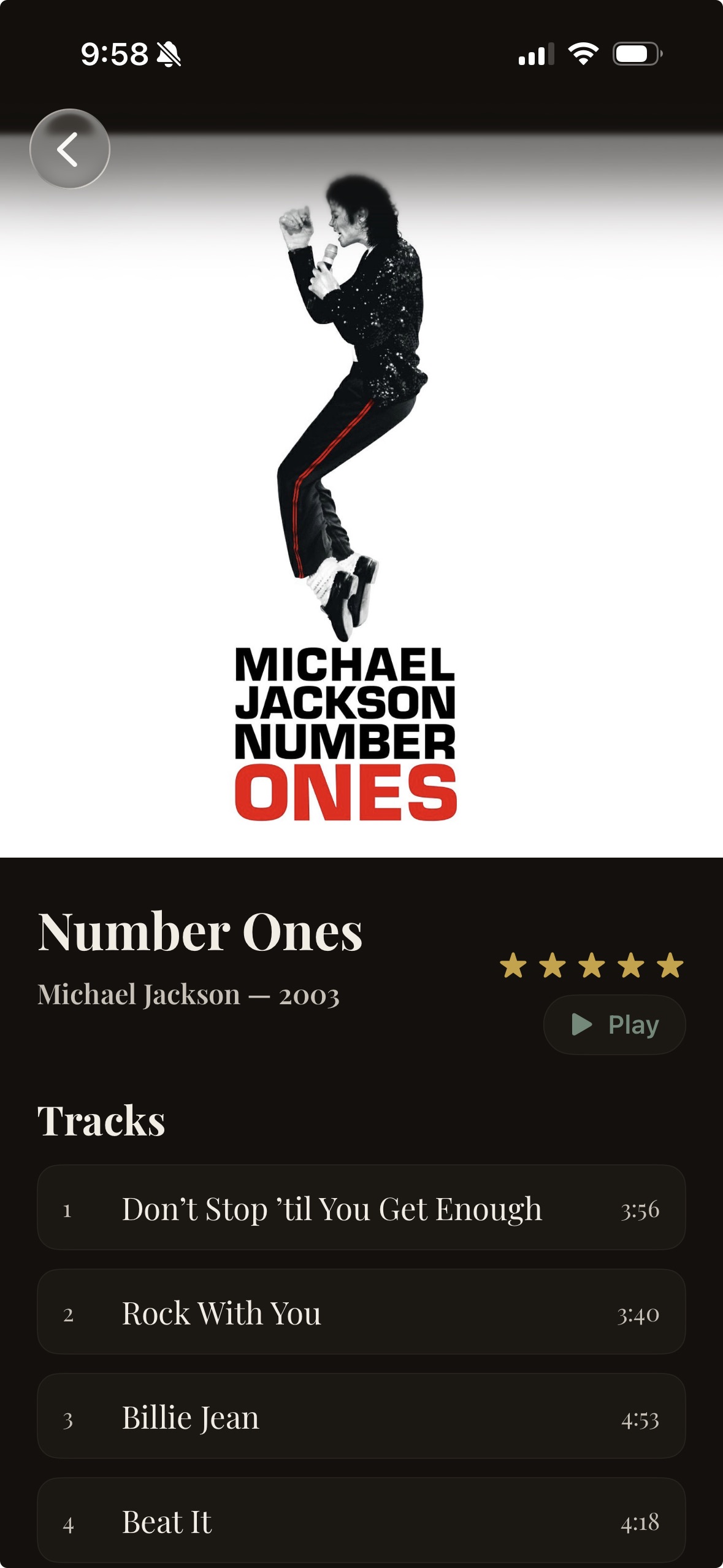

Here's the "album details" page. Again, nothing revolutionary yet... but isn't it cool?

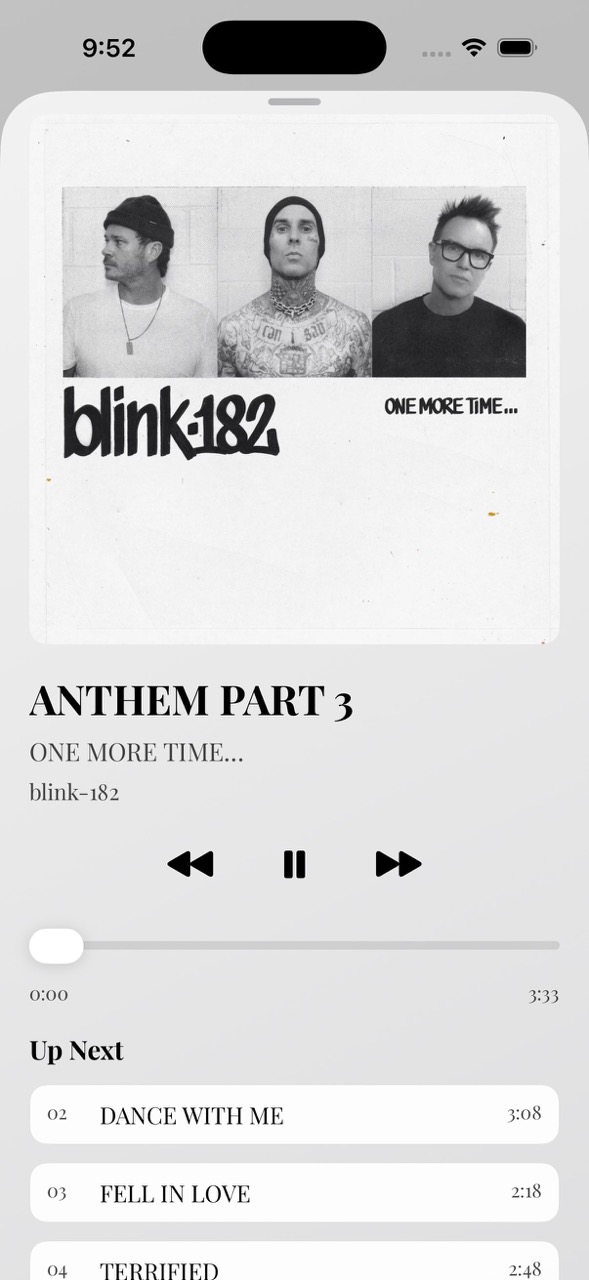

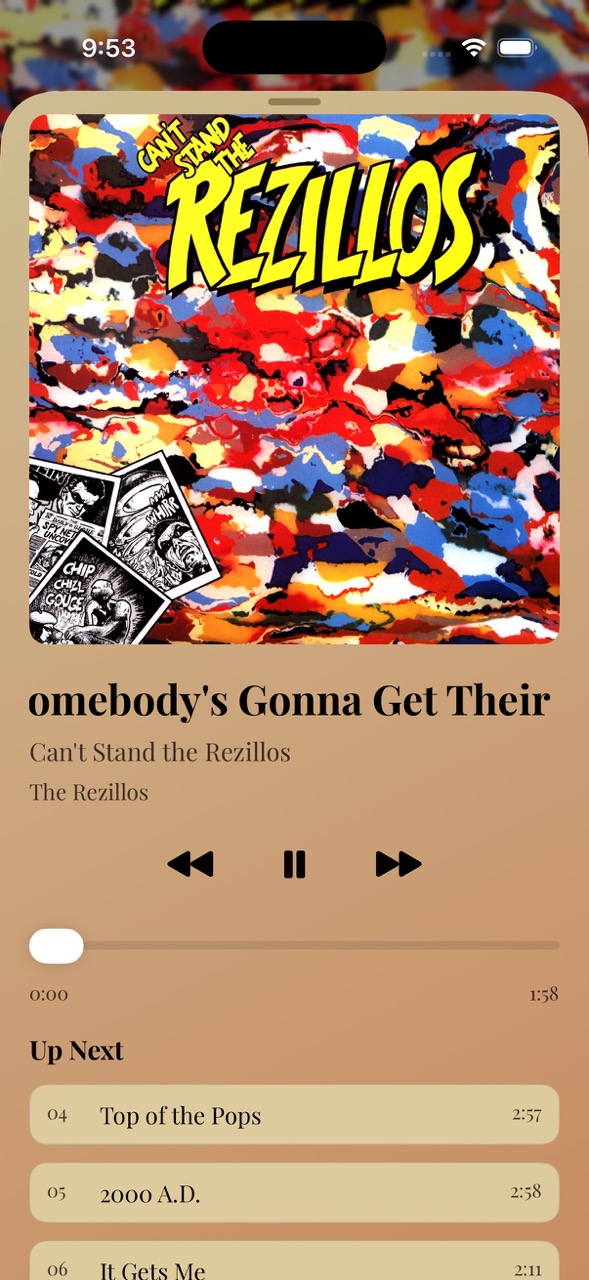

It also actually plays music from the library! Behold: Taco Grande in all it's glory.

Next steps

I stayed up until midnight last night getting this far, and I'm afraid I'll get sucked into a deeper rabbit hole if I don't sign off for now. So here's my next steps:

- Offline media manager. I don't want to be streaming music across the internet if I can help it. I have a beefy drive on my phone, might as well use it.

- Queue manager. I want there to be a queue, should be able to insert albums into the bottom of the queue as needed.

- Now playing screen. I will mostly get close to what Plexamp does for a v1 but just need something in place for now.

- Caching artwork and library metadata. Right now, the app refreshes the library every time I launch the app. I don't update it that often, so I'd like it to do a one-time full sync of everything and then cache that.

- Hand-in-hand with that feature, I want to get a selective sync engine going which periodically detects and refreshes the local cache when there are changes remotely.

- Incorporate with the lock screen's now playing + remote control functionality.

- Get a basic settings screen in place.

Once that's done, I'm going to make this app my daily driver and go from there.

Okay if I don't just go to bed now I'll stay up for another six hours doing this. I haven't had this much fun on a computer in years. Even while writing this blog post I made some tweaks, like adding the track artist to its listing in the show album screen if it differs from the album artist.